CHAPTER 3: THE KAZEM-BEK FAMILY

The Russian Powerbrokers: Alexandr Kazem-Bek, the Chavchavadze, and the Gatchina Group

In this chapter, we discuss the key role played by a group of people interconnected by family links, personal friendships, and shared political worldviews. In this group we found many of the main protagonists whose destiny and that of their children we will be following until nowadays: the famous Alexandr Kazem-Bek, the Chavchavadze family and, linked to it, the Klimovs, Boris Glazunov, Nikolai Rutchenko, and Pavel Delle. With one exception, that of Mikhail Chavchavadze, who seems to have worked with Nazi occupants in Paris only for financial reasons, all the other protagonists have been engaged in collaborationism, some with some cautiousness, like Kazem-Bek, others with enthusiasm, in charge of diversion operations on the Eastern Front and then working for the Vlasov army.

The Kazem-Beks belong to a famous Russian aristocratic family of Azerbaijani and Iranian origin, founded in the early 19th century by Muhammad Nazir Khan, paymaster general of the Derbent Khanate. The first Aleksandr Kazem-Bek (1845-1894) was one of the founders of Oriental studies in Russia, a professor of Kazan and St. Petersburg universities.

His son, Lev Aleksandrovich Kazem-Bek (1875-1952), a graduate of the Corp of Pages, was a Director of the State Bank in Kaluga and the Peasants' Land Bank in Tallinn. He was also friend with the late Russian Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin (1862-1911), whose son, Arcadii Stolypin, will be a central figure of our story. In 1919, during the civil war, Lev joined the White Army, and left Russia with his family in early 1920, through Constantinople, Varna, and then Yugoslavia.

Eventually arriving in Budapest, he was very politically active, leading the Russian Monarchical Club that contacted Aufbau leader, Max Erwin von Scheubner-Richter. Shortly before Rathenau’s assassination on June 24, 1922, a high-level Aufbau delegation — that included First Lieutenant Scheubner-Richter, General Vassili Biskupskii (1878–1945), and the Ukrainian Cossack leader, Colonel Ivan Poltavets-Ostranitsa — arrived in Budapest to hold talks with Lev Kazem-Bek. Lev also played a key role in the November 1922 monarchist congress in Paris. In 1923, he moved to France with his daughter, Mara, and settled in Compiègne. In 1941, he was interned by the Germans in the Compiègne prisoner of war (POW) camp. In 1947, he returned to the USSR and was condemned for anti-Soviet activities. Exiled to Kazakhstan, he died of hunger in 1952.

In 1921, his son Alexandr Kazem-Bek (1902–1977) moved to Hungary, where Miklós Horthy’s government was particularly welcoming to White Russians. Alexandr taught French in the city of Pécs and worked as a secretary for Prince Dimitrii Petrovitch Golitsyn-Muravlin (Pseudonym: Muravlin, 1860-1928),¹ who led the original Black Hundred organization in tsarist Russia. Prince Golitsyn became the political representative of Grand Duke Kirill at the beginning of 1922 and handed over the direction of Grand Duke Kirill’s chancellery to Colonel E. Dolivo-Dolinskii, the former deputy to General Anton Denikin.

Thanks to Golitsyn, Alexandr Kazem-Bek entered the circles supporting Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich.² He then spent some time in Volhynia at his in-law’s property before going to Munich to study in late 1922. In 1923, Alexandr and his wife moved to Paris and then to Beausoleil, near Monaco. Alexandr met Grand Duke Kirill and his wife Victoria for the first time in early 1924 and remained under their influence — especially Victoria’s — for a long period of time.

Victoria, Kazem-Bek, and the birth of the Mladorossy

Victoria pushed for younger generations of Russian émigrés to join the political fight and, therefore, became a fervent supporter of Kazem-Bek’s main initiative, the Mladorossy (Young Russians). Already in 1920, at the First Congress of the Union of Russian Youth, young people such as Kazem-Bek expressed their dissatisfaction with their fathers and their bygone ideological fights. In February 1923, Victoria funded a new Congress in Munich for the pro-Kirill sections of White emigration, which give birth to the Mladorossy. The organizing committee included Kazem-Bek as Treasurer; Sergey Mikhailovich Tolstoi-Miloslavskii, Kazem-Bek’s cousin, as President; Prince Sergei Sergeevich Obolenskii (1908–1980), Kazem-Bek’s cousin by alliance; and several of his friends, including Boris K. Likhachov, Prince Konstantin Nikolaevich Engalitchev, and Vsevolod Ulievich Variagin. Both of the Obolensky brothers, Sergei and Lev, were employed in Leuchtenberg’s Banque Slave du Midi. Kazem-Bek took lead of the new organization, at first called Young Russia (Molodaia Rossiia) and renamed it, The Union of the Young Russians (Soiuz Mladorossov). A new Congress was organized in Paris in 1924, and Kazem-Bek was reelected as leader of the movement. The Mladorossy headquarter was later transferred to his own address in Le Vésinet.

In the beginning, the Mladorossy was only one of many competing movements trying to unify the Russian émigrés. Yet the Mladorossy benefited from Victoria’s activism, as well as support from some members of the Romanov family, such as the Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, Kirill’s cousin, and Grand Duke’s Andrei Vladimirovich, Kirill’s brother.³ In 1929, the death of Kirill’s competitor for the throne, Nikolai Nikolaievich, as well as the arrival in Saint Briac of Queen Marie of Romania, Victoria’s sister and someone who could help the White cause financially, boosted the Mladorossy on the émigré scene.

In the early 1930, the Mladorossy could count about 600 members in France, 350 in Czechoslovakia, 200 in Yugoslavia, 150 in Bulgaria, and about 100 in the other European countries.⁴ Yet, a new competitor rapidly arrived: the NTS was launched in 1930 and separated itself from the Mladorossy because of its refusal to take a position on the future government of a post-Bolshevik Russia and because it called for terrorist actions within the Soviet Union. Both groups attacked members of the other group at the exits of religious offices, especially at the Daru Street Orthodox Church in Paris.⁵

Unsuccessful attempts at getting Nazi support

Despite their unsuccessful approaches to the National Socialists, the Mladorossy saw the situation as conducive to supporting efforts to form a “Russian National United Front” that aimed to strengthen contacts with existing Russian fascist or Nazi parties.⁶ As early as 1931, Kazem-Bek met Anastasii Vonsiastskii in Paris, but the latter did not bring any financial support. He also met with Konstantin Rodzaevskii from the Russian Fascist Party in the spring of 1933. The time had come to form a “Fascist United Front” which, with the help of the Germans in the west and Japan in the east, would encircle the Soviets. Vonsiatsky, therefore, resumed contact with Kazem-Bek on July 22, 1933. In the middle of September 1933, Vonsiatskii met once again Kazem-Bek in Paris, and together they went to Berlin.⁷

On September 22, the conference that brought together the three movements took place at the ROND headquarters in Berlin-Wilmersdorf. It included:

Four days after the Berlin conference, the ROND was banned by the Prussian government under pressure from the Soviets, who had expelled German press correspondents from Moscow.⁹ Vonsiatskii continued to maintain cordial relations with Kazem-Bek until 1934.¹⁰ Relations between Mladorossy and the Kharbin-based Russian Fascist Party remained platonic, but the two movements soon became rivals in the major cities of the Far East.¹¹

In 1933, the Mladorossy newspaper Iskra published several positive comments on the Nazi victory and their ascent to power. In February, just a few days after Hitler’s victory, the Mladorossy addressed a congratulatory message to the new Chancellor, as well as to his Minister of Foreign Affairs, Konstantin von Neurath.¹² In March, Boris Likhachov, representing the movement in Germany, tried to be in touch with the NSDAP Office of Foreign Affairs (Außenpolitische Amt der NSDAP) led by Alfred Rosenberg, and also sent two letters to Hitler, announcing that, given the political changes, the Mladorossy intended to move its center from Paris to Berlin—requests that were politely rejected by the NSDAP, which was not interested in collaborating with the Mladorossy. At the same time, Kazem-Bek’s competitor, General Biskupskii, also launched an operation to charm the Nazis, proposing to transform the Mladorossy into a secret intelligence cell at the service of Rosenberg’s Office of Foreign Affairs.

With France’s entry into war, Kazem-Bek decided to dissolve the Mladorossy in May 1940. The organization went underground, headed by Nikolai Dulger-Sheiken, and would be officially reconstituted in 1945 as the “Russian Revolutionnary Forces” (RRF), led by Dulger-Sheiken and Georgii Knupffer.¹³ On June 10, 1940, a few days before Nazi troops entered Paris, approximately 30 Mladorossy, including Kazem-Bek, were arrested by French police, likely for their pro-Soviet (and, at that time, pro-German, stance, since the Soviet Union was allied with Germany).¹⁴ Through the Aubert League connections, Kazem-Bek’s spouse Svetlana got in touch with Marshal Pétain and Pierre Laval. She went to Laval’s house and was received by his daughter Josée, who recommended that she go look for her father directly in Vichy. Svetlana traveled to Vichy where she was received by Pétain himself, as he “knew Kazem-Bek personally.” Thanks to Alexandr Mikhailovich Putianin (1897–1954) and his wife’s intervention, Svetlana received an official document signed by Pétain and Laval ordering the release of Kazem-Bek, Putiatin, and Konstantin Shibanov from the Vernet camp.¹⁵

From France to the U.S.: Kazem-Bek working for U.S. intelligence agencies

With the help of Paul Anderson,¹⁶ Kazem-Bek left France on September 10, 1941, crossing the Atlantic by boat to New York. On the day of his arrival, October 4, he published an appeal in several Russian- and English-language newspapers stating that he was “at the disposal of the American authorities to best serve the cause that America and its great president intend to defend.”¹⁷ The declaration was allegedly forwarded to U.S. policy circles.¹⁸ Kazem-Bek also went to Washington D.C. upon his arrival in the U.S. to “make contact with American government circles.” He was received by “several Russians” [no names], but none of them responded to his request.¹⁹

In November 1941 Kazem-Bek was admitted as a volunteer informant for the Coordinator of Information (COI), a civilian intelligence agency reporting directly to President Roosevelt.²⁰ He benefitted from three recommendations: from Henry de Bach, an old friend of Kazem-Bek’s and a former advisor to the Russian Embassy in Washington D.C.;²¹ from Boris Bakhmeteff, the former ambassador; and from Bakhmeteff’s uncle, Basile Hwoschinskii, the vice president of the foreign section of the Hanover Bank in New York.

Kazem-Bek was then summoned to Washington D.C., where he was asked to prepare reports on organizations or individuals he knew.²² His contact at the COI in New York was a man named Peter Karlow.²³ Kazem-Bek had also been contacted by a rival service, the Military Intelligence of New York. These two networks were soon forced to collaborate: Kazem-Bek would send copies of the reports he made for the COI to the Military Intelligence. His contact at the NYC Military Intelligence was DeWitt Clinton Poole, former Consul General in Moscow in 1917 and a friend of Paul Anderson.²⁴

In December 1941, Kazem-Bek also sent two telegrams to President Roosevelt: one under his own name saying he “considers it a privilege and a personal duty to engage in the accomplishment of the great task which now unites the Russian and American nations in the struggle against their common enemies,”²⁵ and another one as a member of the NYC-based Society of Friends of Russian Culture, along with other members of the Society—Nikolay Vakar, member of the Mladorossy NYC chapter, and Henry de Bach.²⁶

In January 1942, Kazem-Bek gave a series of lectures in Detroit, where several members of the Mladorossy chapter were employed at the Ford factory. In a letter to his wife, Svetlana, Kazem-Bek said that he was able to meet “a collaborator and advisor of Henry Ford, Cameron, who proposed to meet Ford in person.” Later in Kazem-Bek’s biography, Mireille Massip specifies that this meeting never took place.²⁷

After looking for several jobs, in the fall of 1942, Kazem-Bek moved to San Francisco to work night shifts for Bank of America; this left him time during the day to write articles for Novaia Zaria and print them at the Bank during his shift.²⁸ Beginning in August or September 1942, he was contacted by the OSS [successor to the COI] and asked to address questions relating to the situation in Russia. His contact for the OSS in Washington D.C. was a man named Lovering Hill.²⁹ A few months later, in January 1943, Kazem-Bek also began providing reports to the War Department in San Francisco.³⁰ He was in contact specifically with Captain Lansdale.³¹

In 1944, Kazem-Bek was contacted by Franklin Edgerton of the Department of Oriental Studies of Yale University, who wanted to recruit Kazem-Bek as an instructor for the Russian language courses that Yale organized for the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP).³² ³³ Kazem-Bek’s wife, Svetlana, found a job as an assistant in the same program. In October 1944, Paul Anderson, who, at the time, was the head of the YMCA in Europe and deputy secretary general of War Prisoners’ Aid for Northwest Europe, hired Kazem-Bek as the director of the Book Section of the POW Aid Committee. He was responsible for the books sent to the POWs interned in U.S. camps.³⁴ His position at the YMCA was terminated in early 1946.³⁵

One can conclude from this brief overview of Kazem-Bek’s path before the end of WWII that the man sought partners in his political fight to promote Mladorossy ideology and the demise the Soviet Union. In the 1920s–1930s, he turned toward fascist movements—at first broadly, but then more precisely toward the Nazis—a logical direction given his key role in Grand Duke Kirill’s entourage and his affinity with Victoria, herself once a central supporter of the Nazis. In 1941, once Kazem-Bek decided to move to the U.S., he offered his services to U.S. intelligence agencies, trying to portray the Mladorossy as a democratic opposition to Communism. His trajectory epitomizes the shift of so many White Russians, from supporting fascism to support the U.S. anticommunist struggle.

His son, Lev Aleksandrovich Kazem-Bek (1875-1952), a graduate of the Corp of Pages, was a Director of the State Bank in Kaluga and the Peasants' Land Bank in Tallinn. He was also friend with the late Russian Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin (1862-1911), whose son, Arcadii Stolypin, will be a central figure of our story. In 1919, during the civil war, Lev joined the White Army, and left Russia with his family in early 1920, through Constantinople, Varna, and then Yugoslavia.

Eventually arriving in Budapest, he was very politically active, leading the Russian Monarchical Club that contacted Aufbau leader, Max Erwin von Scheubner-Richter. Shortly before Rathenau’s assassination on June 24, 1922, a high-level Aufbau delegation — that included First Lieutenant Scheubner-Richter, General Vassili Biskupskii (1878–1945), and the Ukrainian Cossack leader, Colonel Ivan Poltavets-Ostranitsa — arrived in Budapest to hold talks with Lev Kazem-Bek. Lev also played a key role in the November 1922 monarchist congress in Paris. In 1923, he moved to France with his daughter, Mara, and settled in Compiègne. In 1941, he was interned by the Germans in the Compiègne prisoner of war (POW) camp. In 1947, he returned to the USSR and was condemned for anti-Soviet activities. Exiled to Kazakhstan, he died of hunger in 1952.

In 1921, his son Alexandr Kazem-Bek (1902–1977) moved to Hungary, where Miklós Horthy’s government was particularly welcoming to White Russians. Alexandr taught French in the city of Pécs and worked as a secretary for Prince Dimitrii Petrovitch Golitsyn-Muravlin (Pseudonym: Muravlin, 1860-1928),¹ who led the original Black Hundred organization in tsarist Russia. Prince Golitsyn became the political representative of Grand Duke Kirill at the beginning of 1922 and handed over the direction of Grand Duke Kirill’s chancellery to Colonel E. Dolivo-Dolinskii, the former deputy to General Anton Denikin.

Thanks to Golitsyn, Alexandr Kazem-Bek entered the circles supporting Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich.² He then spent some time in Volhynia at his in-law’s property before going to Munich to study in late 1922. In 1923, Alexandr and his wife moved to Paris and then to Beausoleil, near Monaco. Alexandr met Grand Duke Kirill and his wife Victoria for the first time in early 1924 and remained under their influence — especially Victoria’s — for a long period of time.

Victoria, Kazem-Bek, and the birth of the Mladorossy

Victoria pushed for younger generations of Russian émigrés to join the political fight and, therefore, became a fervent supporter of Kazem-Bek’s main initiative, the Mladorossy (Young Russians). Already in 1920, at the First Congress of the Union of Russian Youth, young people such as Kazem-Bek expressed their dissatisfaction with their fathers and their bygone ideological fights. In February 1923, Victoria funded a new Congress in Munich for the pro-Kirill sections of White emigration, which give birth to the Mladorossy. The organizing committee included Kazem-Bek as Treasurer; Sergey Mikhailovich Tolstoi-Miloslavskii, Kazem-Bek’s cousin, as President; Prince Sergei Sergeevich Obolenskii (1908–1980), Kazem-Bek’s cousin by alliance; and several of his friends, including Boris K. Likhachov, Prince Konstantin Nikolaevich Engalitchev, and Vsevolod Ulievich Variagin. Both of the Obolensky brothers, Sergei and Lev, were employed in Leuchtenberg’s Banque Slave du Midi. Kazem-Bek took lead of the new organization, at first called Young Russia (Molodaia Rossiia) and renamed it, The Union of the Young Russians (Soiuz Mladorossov). A new Congress was organized in Paris in 1924, and Kazem-Bek was reelected as leader of the movement. The Mladorossy headquarter was later transferred to his own address in Le Vésinet.

In the beginning, the Mladorossy was only one of many competing movements trying to unify the Russian émigrés. Yet the Mladorossy benefited from Victoria’s activism, as well as support from some members of the Romanov family, such as the Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, Kirill’s cousin, and Grand Duke’s Andrei Vladimirovich, Kirill’s brother.³ In 1929, the death of Kirill’s competitor for the throne, Nikolai Nikolaievich, as well as the arrival in Saint Briac of Queen Marie of Romania, Victoria’s sister and someone who could help the White cause financially, boosted the Mladorossy on the émigré scene.

In the early 1930, the Mladorossy could count about 600 members in France, 350 in Czechoslovakia, 200 in Yugoslavia, 150 in Bulgaria, and about 100 in the other European countries.⁴ Yet, a new competitor rapidly arrived: the NTS was launched in 1930 and separated itself from the Mladorossy because of its refusal to take a position on the future government of a post-Bolshevik Russia and because it called for terrorist actions within the Soviet Union. Both groups attacked members of the other group at the exits of religious offices, especially at the Daru Street Orthodox Church in Paris.⁵

Unsuccessful attempts at getting Nazi support

Despite their unsuccessful approaches to the National Socialists, the Mladorossy saw the situation as conducive to supporting efforts to form a “Russian National United Front” that aimed to strengthen contacts with existing Russian fascist or Nazi parties.⁶ As early as 1931, Kazem-Bek met Anastasii Vonsiastskii in Paris, but the latter did not bring any financial support. He also met with Konstantin Rodzaevskii from the Russian Fascist Party in the spring of 1933. The time had come to form a “Fascist United Front” which, with the help of the Germans in the west and Japan in the east, would encircle the Soviets. Vonsiatsky, therefore, resumed contact with Kazem-Bek on July 22, 1933. In the middle of September 1933, Vonsiatskii met once again Kazem-Bek in Paris, and together they went to Berlin.⁷

On September 22, the conference that brought together the three movements took place at the ROND headquarters in Berlin-Wilmersdorf. It included:

- The ROND delegation, including President Bermondt-Avalov; A. Meller-Zakomelskii, the Secretary of the Higher Council; N. Kastel, a member of the Board of Governors, B. Sobinov, director of the political section; V. Golovachev, leader for the region of Berlin; as well as A. Averkiev, E. Varanitsa and A. Zhemchuzhnikov.

- The Mladorossy delegation, including: Alexandr Kazem-Bek, with the support of Grand Duke Kirill; S. Obolenskii, representative of the Mladorossy in Germany; and Gleb Boletskii, representative of the Mladorossy in Lithuania.

- Anastasii Vonsiatskii.⁸

Four days after the Berlin conference, the ROND was banned by the Prussian government under pressure from the Soviets, who had expelled German press correspondents from Moscow.⁹ Vonsiatskii continued to maintain cordial relations with Kazem-Bek until 1934.¹⁰ Relations between Mladorossy and the Kharbin-based Russian Fascist Party remained platonic, but the two movements soon became rivals in the major cities of the Far East.¹¹

In 1933, the Mladorossy newspaper Iskra published several positive comments on the Nazi victory and their ascent to power. In February, just a few days after Hitler’s victory, the Mladorossy addressed a congratulatory message to the new Chancellor, as well as to his Minister of Foreign Affairs, Konstantin von Neurath.¹² In March, Boris Likhachov, representing the movement in Germany, tried to be in touch with the NSDAP Office of Foreign Affairs (Außenpolitische Amt der NSDAP) led by Alfred Rosenberg, and also sent two letters to Hitler, announcing that, given the political changes, the Mladorossy intended to move its center from Paris to Berlin—requests that were politely rejected by the NSDAP, which was not interested in collaborating with the Mladorossy. At the same time, Kazem-Bek’s competitor, General Biskupskii, also launched an operation to charm the Nazis, proposing to transform the Mladorossy into a secret intelligence cell at the service of Rosenberg’s Office of Foreign Affairs.

With France’s entry into war, Kazem-Bek decided to dissolve the Mladorossy in May 1940. The organization went underground, headed by Nikolai Dulger-Sheiken, and would be officially reconstituted in 1945 as the “Russian Revolutionnary Forces” (RRF), led by Dulger-Sheiken and Georgii Knupffer.¹³ On June 10, 1940, a few days before Nazi troops entered Paris, approximately 30 Mladorossy, including Kazem-Bek, were arrested by French police, likely for their pro-Soviet (and, at that time, pro-German, stance, since the Soviet Union was allied with Germany).¹⁴ Through the Aubert League connections, Kazem-Bek’s spouse Svetlana got in touch with Marshal Pétain and Pierre Laval. She went to Laval’s house and was received by his daughter Josée, who recommended that she go look for her father directly in Vichy. Svetlana traveled to Vichy where she was received by Pétain himself, as he “knew Kazem-Bek personally.” Thanks to Alexandr Mikhailovich Putianin (1897–1954) and his wife’s intervention, Svetlana received an official document signed by Pétain and Laval ordering the release of Kazem-Bek, Putiatin, and Konstantin Shibanov from the Vernet camp.¹⁵

From France to the U.S.: Kazem-Bek working for U.S. intelligence agencies

With the help of Paul Anderson,¹⁶ Kazem-Bek left France on September 10, 1941, crossing the Atlantic by boat to New York. On the day of his arrival, October 4, he published an appeal in several Russian- and English-language newspapers stating that he was “at the disposal of the American authorities to best serve the cause that America and its great president intend to defend.”¹⁷ The declaration was allegedly forwarded to U.S. policy circles.¹⁸ Kazem-Bek also went to Washington D.C. upon his arrival in the U.S. to “make contact with American government circles.” He was received by “several Russians” [no names], but none of them responded to his request.¹⁹

In November 1941 Kazem-Bek was admitted as a volunteer informant for the Coordinator of Information (COI), a civilian intelligence agency reporting directly to President Roosevelt.²⁰ He benefitted from three recommendations: from Henry de Bach, an old friend of Kazem-Bek’s and a former advisor to the Russian Embassy in Washington D.C.;²¹ from Boris Bakhmeteff, the former ambassador; and from Bakhmeteff’s uncle, Basile Hwoschinskii, the vice president of the foreign section of the Hanover Bank in New York.

Kazem-Bek was then summoned to Washington D.C., where he was asked to prepare reports on organizations or individuals he knew.²² His contact at the COI in New York was a man named Peter Karlow.²³ Kazem-Bek had also been contacted by a rival service, the Military Intelligence of New York. These two networks were soon forced to collaborate: Kazem-Bek would send copies of the reports he made for the COI to the Military Intelligence. His contact at the NYC Military Intelligence was DeWitt Clinton Poole, former Consul General in Moscow in 1917 and a friend of Paul Anderson.²⁴

In December 1941, Kazem-Bek also sent two telegrams to President Roosevelt: one under his own name saying he “considers it a privilege and a personal duty to engage in the accomplishment of the great task which now unites the Russian and American nations in the struggle against their common enemies,”²⁵ and another one as a member of the NYC-based Society of Friends of Russian Culture, along with other members of the Society—Nikolay Vakar, member of the Mladorossy NYC chapter, and Henry de Bach.²⁶

In January 1942, Kazem-Bek gave a series of lectures in Detroit, where several members of the Mladorossy chapter were employed at the Ford factory. In a letter to his wife, Svetlana, Kazem-Bek said that he was able to meet “a collaborator and advisor of Henry Ford, Cameron, who proposed to meet Ford in person.” Later in Kazem-Bek’s biography, Mireille Massip specifies that this meeting never took place.²⁷

After looking for several jobs, in the fall of 1942, Kazem-Bek moved to San Francisco to work night shifts for Bank of America; this left him time during the day to write articles for Novaia Zaria and print them at the Bank during his shift.²⁸ Beginning in August or September 1942, he was contacted by the OSS [successor to the COI] and asked to address questions relating to the situation in Russia. His contact for the OSS in Washington D.C. was a man named Lovering Hill.²⁹ A few months later, in January 1943, Kazem-Bek also began providing reports to the War Department in San Francisco.³⁰ He was in contact specifically with Captain Lansdale.³¹

In 1944, Kazem-Bek was contacted by Franklin Edgerton of the Department of Oriental Studies of Yale University, who wanted to recruit Kazem-Bek as an instructor for the Russian language courses that Yale organized for the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP).³² ³³ Kazem-Bek’s wife, Svetlana, found a job as an assistant in the same program. In October 1944, Paul Anderson, who, at the time, was the head of the YMCA in Europe and deputy secretary general of War Prisoners’ Aid for Northwest Europe, hired Kazem-Bek as the director of the Book Section of the POW Aid Committee. He was responsible for the books sent to the POWs interned in U.S. camps.³⁴ His position at the YMCA was terminated in early 1946.³⁵

One can conclude from this brief overview of Kazem-Bek’s path before the end of WWII that the man sought partners in his political fight to promote Mladorossy ideology and the demise the Soviet Union. In the 1920s–1930s, he turned toward fascist movements—at first broadly, but then more precisely toward the Nazis—a logical direction given his key role in Grand Duke Kirill’s entourage and his affinity with Victoria, herself once a central supporter of the Nazis. In 1941, once Kazem-Bek decided to move to the U.S., he offered his services to U.S. intelligence agencies, trying to portray the Mladorossy as a democratic opposition to Communism. His trajectory epitomizes the shift of so many White Russians, from supporting fascism to support the U.S. anticommunist struggle.

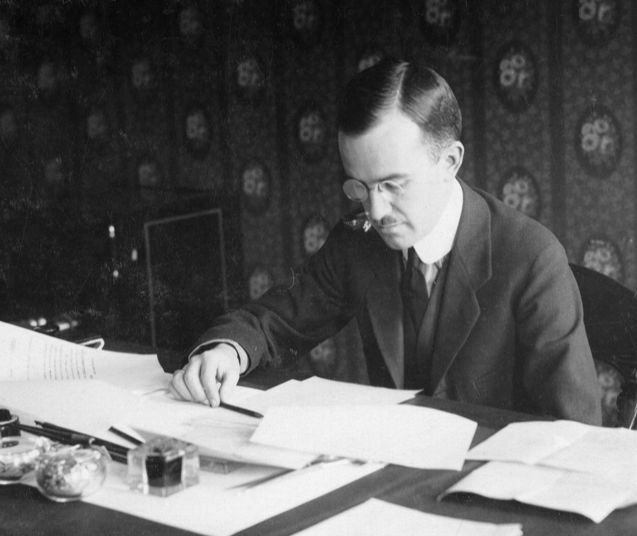

Aleksandr Kazem-Bek (1845-1894)

Source

Source

Alexandr Kazem-Bek (1902-1977)

Source

Source

Participants of the Trilateral Conference in Berlin in 1933. In the center, under a two-headed eagle, is the leader of the Russian National Socialist Movement Pavel Bermondt-Avalov, to his right Aleksandr Kazem-Bek, to his left Anastasii Vonsiatskii.

Source

Source

Chapter Content

The Kazem-Bek Family

Explore the networks, citations, and documents using the buttons on the right

Lev Kazem-Bek (1875-1952)

Source

Source

Issue of the Mladorosskaia Iskra

Source

Source

Russian emigres in New York

Source

Source

DeWitt Clinton Poole (1885-1952)

Source

Source

Content Oriented Web

Make great presentations, longreads, and landing pages, as well as photo stories, blogs, lookbooks, and all other kinds of content oriented projects.

Content Oriented Web

Make great presentations, longreads, and landing pages, as well as photo stories, blogs, lookbooks, and all other kinds of content oriented projects.

Tilda Publishing

Appendix 1

NKVD document on Oleg Klimov

Appendix 2

Poland’s support for Georgian independence and anti-Soviet activities

Interwar Poland and the Intermarium Idea

Appendix 3

Appendix 4

Tilda Publishing

Georgian Collaborationism

Appendix 4

Tilda Publishing

Excerpts of Ruchenko memoirs

Appendix 5

Vineta Operation

Tilda Publishing

A report from the Kiev NKVD surveillance on Herman Strekker

Appendix 6

Content Oriented Web

Make great presentations, longreads, and landing pages, as well as photo stories, blogs, lookbooks, and all other kinds of content oriented projects.

[1] Massip, Mirey. Istina - doch’ vremeni: Aleksandr Kazem-Bek i russkaya emigratsiya na Zapade. Moskva: YAzyki slavyanskoy kul’tury, 2010,102–103.

[2] Massip, Istina - doch’ vremeni. 113.

[3] Massip, Istina - doch’ vremeni, 187.

[4] Massip, Istina - doch’ vremeni, 194.

[5] Massip, Istina - doch’ vremeni, 209-210.

[6] Massip, Istina - doch’ vremeni, 225.

[7] Massip, Istina - doch’ vremeni, 228-229.

[8] Massip, Istina - doch’ vremeni, 229.

[9] Massip, Istina - doch’ vremeni, 230.

[10] Massip, Istina - doch’ vremeni, 234.

[11] Massip, Istina - doch’ vremeni, 235.

[12] Massip, Istina - doch’ vremeni, 224.

[13] Dorril, Stephen. ‘Chapter 20: The NTS and Young Russians’. In MI6: Inside the Covert World of Her Majesty’s Secret Intelligence Service. New York: Free Press, 2000.

[14] Massip, Istina - doch’ vremeni, 337.

[15] Massip, Istina - doch’ vremeni, 341-354.

[16] Massip, Mireille La vérité est fille du temps: Alexandre Kazem-Beg et l’émigration Russe en Occident. Georg ed., 1999. 364.

[17] Massip, La vérité est fille du temps, 367.

[18] Massip, La vérité est fille du temps, 370.

[19] Massip, La vérité est fille du temps, 368-370.

[20] Massip, La vérité est fille du temps, 372. On June 13, 1942, Roosevelt split the functions and created two new agencies: the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), a predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency, and the Office of War Information, a predecessor of the United States Information Agency.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Massip, La vérité est fille du temps, 371-372

[23] Massip, La vérité est fille du temps, 379.

[24] Massip, La vérité est fille du temps, 373.

[25] Massip, La vérité est fille du temps, 371.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Massip, La vérité est fille du temps, 373-375.

[28] Massip, La vérité est fille du temps, 395.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Massip, La vérité est fille du temps, 404.

[31] Massip, La vérité est fille du temps, 408.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Massip, La vérité est fille du temps, 412.

[34] Massip, La vérité est fille du temps, 423.

[35] Massip, La vérité est fille du temps, 435.

[2] Massip, Istina - doch’ vremeni. 113.

[3] Massip, Istina - doch’ vremeni, 187.

[4] Massip, Istina - doch’ vremeni, 194.

[5] Massip, Istina - doch’ vremeni, 209-210.

[6] Massip, Istina - doch’ vremeni, 225.

[7] Massip, Istina - doch’ vremeni, 228-229.

[8] Massip, Istina - doch’ vremeni, 229.

[9] Massip, Istina - doch’ vremeni, 230.

[10] Massip, Istina - doch’ vremeni, 234.

[11] Massip, Istina - doch’ vremeni, 235.

[12] Massip, Istina - doch’ vremeni, 224.

[13] Dorril, Stephen. ‘Chapter 20: The NTS and Young Russians’. In MI6: Inside the Covert World of Her Majesty’s Secret Intelligence Service. New York: Free Press, 2000.

[14] Massip, Istina - doch’ vremeni, 337.

[15] Massip, Istina - doch’ vremeni, 341-354.

[16] Massip, Mireille La vérité est fille du temps: Alexandre Kazem-Beg et l’émigration Russe en Occident. Georg ed., 1999. 364.

[17] Massip, La vérité est fille du temps, 367.

[18] Massip, La vérité est fille du temps, 370.

[19] Massip, La vérité est fille du temps, 368-370.

[20] Massip, La vérité est fille du temps, 372. On June 13, 1942, Roosevelt split the functions and created two new agencies: the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), a predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency, and the Office of War Information, a predecessor of the United States Information Agency.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Massip, La vérité est fille du temps, 371-372

[23] Massip, La vérité est fille du temps, 379.

[24] Massip, La vérité est fille du temps, 373.

[25] Massip, La vérité est fille du temps, 371.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Massip, La vérité est fille du temps, 373-375.

[28] Massip, La vérité est fille du temps, 395.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Massip, La vérité est fille du temps, 404.

[31] Massip, La vérité est fille du temps, 408.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Massip, La vérité est fille du temps, 412.

[34] Massip, La vérité est fille du temps, 423.

[35] Massip, La vérité est fille du temps, 435.