CHAPTER 2: THE RUSSIAN ARMY IN EXILE

After the defeat of the White Armies in November 1920, the forces of General Wrangel were evacuated from Crimea to Constantinople, and then moved on to Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, and Bulgaria in March 1921. From there, three branching points emerge: in 1924, those who eventually moved on to France founded the Russian All-Military Union (Russkii Obshche-Voinskii Soiuz, ROVS); in 1930, those who stayed in Bulgaria founded the predecessor of the People's Labor Union (Narodno-Trudovoi Soiuz, NTS); the few people who moved to Berlin in 1922 founded the Brotherhood of Russian Truth (Bratsvo Russkoi Pravdy, BRP) in 1924.

The ROVS, the BRP, and the NTS were underground organizations whose purpose was to send agents across the border to the USSR to perform subversion and terror. But another goal of these trips was to bring back intelligence from across enemy lines. These activities made them desirable to foreign intelligence services, notably the 2nd Department of the Polish General Staff (Oddział II Sztabu Generalnego Wojska Polskiego, or Dwojka) responsible for military intelligence. Additionally, all three organizations worked extensively with the Entente Internationale Anticommuniste, an intelligence organization co-founded by a White Russian, Yurii Lodygenskii, and the Swiss lawyer involved in the Conradi Affair, Théodore Aubert.

The ROVS, the BRP, and the NTS were underground organizations whose purpose was to send agents across the border to the USSR to perform subversion and terror. But another goal of these trips was to bring back intelligence from across enemy lines. These activities made them desirable to foreign intelligence services, notably the 2nd Department of the Polish General Staff (Oddział II Sztabu Generalnego Wojska Polskiego, or Dwojka) responsible for military intelligence. Additionally, all three organizations worked extensively with the Entente Internationale Anticommuniste, an intelligence organization co-founded by a White Russian, Yurii Lodygenskii, and the Swiss lawyer involved in the Conradi Affair, Théodore Aubert.

The White Exodus, 1920

Source

Source

Evacuation from Gallipoli to Bulgaria (1921)

Source

Source

Chapter Content

The Russian Army in Exile

Explore the networks, refernces, and documents using buttons on the right

The White Army in Constantinople and the French (1920)

After their evacuation from the Crimea by sea, Pyotr Nikolaevich Wrangel (1878–1928) and his army traveled to Constantinople between November 13 and 16, 1920.¹ Once there, the army came under the protection of the French, whose troops had occupied the city and surrounding area after the defeat of the Turks in World War I (WWI). The French had previously supported Wrangel’s government in the Crimea, but they now decided that, with the defeat of Wrangel, the White Army should be disbanded.²

The reason for this backpedaling was twofold: first, the maintenance of Russian refugees in Turkey fell on France, and, by mid-January 1921, France had spent 100 million francs on this. Approximately the same amount of money was estimated for the property transferred to them by Wrangel³. Therefore, the French authorities felt that they did not have to continue to bear the costs of the Russian refugees.⁴ Secondly, in 1921, France was involved in the Turkish War of Independence (1919–1923) against Mustafa Kemal (Ataturk) and his Turkish National Liberation Movement. Since historically the Russians had always wanted a piece of Turkish territory as well, by sending them to the Aegean Sea, France was getting rid of a rival for Turkish lands.

The “Gallipoli Miracle”

The reorganized army⁵ was distributed among various camps: 20,000 men were sent 1000km to the northwest of Constantinople, to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (Yugoslavia), which had agreed to accept a limited number of refugees. The rest of the troops were sent to three locations: the Don Cossack Corps to various camps in the region of Chatalga, northwest of Constantinople; the First Army Corps to Gallipoli; and the Kuban Cossack Corps to the island of Lemnos, 500 km to the west of Constantinople in the Aegean Sea.⁶

Because the French wanted to disband the Russian Army, they exerted considerable pressure on its men to accept repatriation to Soviet Russia. On Lemnos, the morale of the Cossack troops disintegrated and many accepted repatriation.

At Gallipoli, however, the First Army Corps claimed to have undergone a spiritual and moral revitalization, known as the “Gallipoli Miracle”⁷ that renewed their determination to continue the struggle against the Bolsheviks.⁸ The First Army Corps was the most cohesive unit partly because it contained a disproportionate number of officers. They also were highly motivated to fight and refused repatriation, in large part due to the charisma of their leader, General Alexandr Pavlovich Kutepov (1882–1930), the future leader of the Russian All-Military Union (ROVS) after Wrangel.

This mythology was promoted by the Society of Gallipolians (Obshchestvo Gallipoliitsev), a group established by Kutepov just before he departed Gallipoli in November 1921. The Society kept the veterans of the First Army Corps in touch with one another as they dispersed across Europe and sought to maintain the “Gallipoli spirit” among them.⁹ The vast majority of the members of the Russian All‑Military Union (ROVS), when it was created in 1924, came from the First Army Corps and were also members of the Society of Gallipolians.

Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, and Bulgaria (1921)

From Lemnos and Gallipoli, the remnants of Wrangel’s army were moved, between August and December 1921, to Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, and Bulgaria.¹⁰

¹¹ In each of these three countries, the White Army received financial assistance from local governments. All three also agreed that the immigrated units would keep their command structure, unlike the French, who wanted the army disbanded so as not to pose a rival military threat. By December 1921, approximately only 45,000 men remained in the Army out of the 100,000 who had left the Crimea.¹²

In Yugoslavia, General Pavel Nikolaievich Shatilov (1881–1962) met the Yugoslav Prime Minister and Prince Regent, Alexandr I, who agreed¹³ to allow Russian troops into Yugoslavia with their command structure intact.¹⁴ As a result of these agreements, some 25,000 men of the Russian Army found new homes in Yugoslavia. Even though Yugoslavia would reluctantly join the Axis forces in 1940, in the 1920s Yugoslavia was more closely aligned to the Allied forces. In 1927, Alexandr I of Yugoslavia signed a treaty of alliance with France against his arch-enemy, fascist Italy. It is also Alexander I who, in 1934, is assassinated in France along with French Foreign Minister Louis Barthou, who was trying to build an alliance to contain the forces of Nazi Germany.

Negotiations with the Czech government also provided a home for 1,000 Cossacks, some of whom benefited from the subsidized education in Czechoslovakia as part of the ‘Action Russe’ program.¹⁵

The Bulgarian government also agreed to accept troops from the Russian Army, those commanded by Adrian Konstantinovich Guselshchikov. The Chief of Staff of the Bulgarian Army, Nikola Todorov Topaldzhikov, agreed that troops entering Bulgaria should preserve their military organization and command structure. As a result, some 19,000 men of the Russian Army found homes in Bulgaria.¹⁶ The single largest concentration of workers was at the Pernik coal mines.¹⁷

The King of Bulgaria at the time was Boris III (1894–1943), who married Giovanna of Italy, daughter of Victor Emmanuel III, the main supporter of Mussolini and who was known for his public silence when Mussolini's Fascist government issued its notorious racial purity laws. Notably, Boris III was also favorable to the Nazi regime: on September 7, 1940, an agreement was signed between Hitler and Boris III for the return of the land of Southern Dobruja to Bulgaria, in return for which, Bulgaria had to adopt the anti-Jewish racial “Law for Protection of the Nation”(Zakon za zaščista na nacijata — ZZN). In addition, a secret agreement was signed on February 22, 1943, between Hitler's emissary, SS-Hauptsturmführer Theodor Dannecker, and the Bulgarian Commissar for Jewish Affairs, Alexandr Belev, for the deportations of 20,000 Jews from Bulgarian territory. It is also worth noting that Boris III’s father and predecessor, Ferdinand I (1861–1948), born Ferdinand Maximilian Karl Leopold Maria of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, was a relative¹⁸ of Victoria Melita of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, the wife of Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich, who funded the developing NSDAP in the 1920s.

The history of the Russian Army in exile after their evacuation from the Crimea brought about the creation of three important and influential groups: the Russian All-Military Union (ROVS, founded in France in 1924); the predecessor of the People's Labor Union (NTS, founded Bulgaria in 1930); and the Brotherhood of Russian Truth (BRP, founded in Berlin in 1922). All of these organizations were closely interlinked, and often people belonged simultaneously to several of these structures.

After their evacuation from the Crimea by sea, Pyotr Nikolaevich Wrangel (1878–1928) and his army traveled to Constantinople between November 13 and 16, 1920.¹ Once there, the army came under the protection of the French, whose troops had occupied the city and surrounding area after the defeat of the Turks in World War I (WWI). The French had previously supported Wrangel’s government in the Crimea, but they now decided that, with the defeat of Wrangel, the White Army should be disbanded.²

The reason for this backpedaling was twofold: first, the maintenance of Russian refugees in Turkey fell on France, and, by mid-January 1921, France had spent 100 million francs on this. Approximately the same amount of money was estimated for the property transferred to them by Wrangel³. Therefore, the French authorities felt that they did not have to continue to bear the costs of the Russian refugees.⁴ Secondly, in 1921, France was involved in the Turkish War of Independence (1919–1923) against Mustafa Kemal (Ataturk) and his Turkish National Liberation Movement. Since historically the Russians had always wanted a piece of Turkish territory as well, by sending them to the Aegean Sea, France was getting rid of a rival for Turkish lands.

The “Gallipoli Miracle”

The reorganized army⁵ was distributed among various camps: 20,000 men were sent 1000km to the northwest of Constantinople, to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (Yugoslavia), which had agreed to accept a limited number of refugees. The rest of the troops were sent to three locations: the Don Cossack Corps to various camps in the region of Chatalga, northwest of Constantinople; the First Army Corps to Gallipoli; and the Kuban Cossack Corps to the island of Lemnos, 500 km to the west of Constantinople in the Aegean Sea.⁶

Because the French wanted to disband the Russian Army, they exerted considerable pressure on its men to accept repatriation to Soviet Russia. On Lemnos, the morale of the Cossack troops disintegrated and many accepted repatriation.

At Gallipoli, however, the First Army Corps claimed to have undergone a spiritual and moral revitalization, known as the “Gallipoli Miracle”⁷ that renewed their determination to continue the struggle against the Bolsheviks.⁸ The First Army Corps was the most cohesive unit partly because it contained a disproportionate number of officers. They also were highly motivated to fight and refused repatriation, in large part due to the charisma of their leader, General Alexandr Pavlovich Kutepov (1882–1930), the future leader of the Russian All-Military Union (ROVS) after Wrangel.

This mythology was promoted by the Society of Gallipolians (Obshchestvo Gallipoliitsev), a group established by Kutepov just before he departed Gallipoli in November 1921. The Society kept the veterans of the First Army Corps in touch with one another as they dispersed across Europe and sought to maintain the “Gallipoli spirit” among them.⁹ The vast majority of the members of the Russian All‑Military Union (ROVS), when it was created in 1924, came from the First Army Corps and were also members of the Society of Gallipolians.

Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, and Bulgaria (1921)

From Lemnos and Gallipoli, the remnants of Wrangel’s army were moved, between August and December 1921, to Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, and Bulgaria.¹⁰

¹¹ In each of these three countries, the White Army received financial assistance from local governments. All three also agreed that the immigrated units would keep their command structure, unlike the French, who wanted the army disbanded so as not to pose a rival military threat. By December 1921, approximately only 45,000 men remained in the Army out of the 100,000 who had left the Crimea.¹²

In Yugoslavia, General Pavel Nikolaievich Shatilov (1881–1962) met the Yugoslav Prime Minister and Prince Regent, Alexandr I, who agreed¹³ to allow Russian troops into Yugoslavia with their command structure intact.¹⁴ As a result of these agreements, some 25,000 men of the Russian Army found new homes in Yugoslavia. Even though Yugoslavia would reluctantly join the Axis forces in 1940, in the 1920s Yugoslavia was more closely aligned to the Allied forces. In 1927, Alexandr I of Yugoslavia signed a treaty of alliance with France against his arch-enemy, fascist Italy. It is also Alexander I who, in 1934, is assassinated in France along with French Foreign Minister Louis Barthou, who was trying to build an alliance to contain the forces of Nazi Germany.

Negotiations with the Czech government also provided a home for 1,000 Cossacks, some of whom benefited from the subsidized education in Czechoslovakia as part of the ‘Action Russe’ program.¹⁵

The Bulgarian government also agreed to accept troops from the Russian Army, those commanded by Adrian Konstantinovich Guselshchikov. The Chief of Staff of the Bulgarian Army, Nikola Todorov Topaldzhikov, agreed that troops entering Bulgaria should preserve their military organization and command structure. As a result, some 19,000 men of the Russian Army found homes in Bulgaria.¹⁶ The single largest concentration of workers was at the Pernik coal mines.¹⁷

The King of Bulgaria at the time was Boris III (1894–1943), who married Giovanna of Italy, daughter of Victor Emmanuel III, the main supporter of Mussolini and who was known for his public silence when Mussolini's Fascist government issued its notorious racial purity laws. Notably, Boris III was also favorable to the Nazi regime: on September 7, 1940, an agreement was signed between Hitler and Boris III for the return of the land of Southern Dobruja to Bulgaria, in return for which, Bulgaria had to adopt the anti-Jewish racial “Law for Protection of the Nation”(Zakon za zaščista na nacijata — ZZN). In addition, a secret agreement was signed on February 22, 1943, between Hitler's emissary, SS-Hauptsturmführer Theodor Dannecker, and the Bulgarian Commissar for Jewish Affairs, Alexandr Belev, for the deportations of 20,000 Jews from Bulgarian territory. It is also worth noting that Boris III’s father and predecessor, Ferdinand I (1861–1948), born Ferdinand Maximilian Karl Leopold Maria of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, was a relative¹⁸ of Victoria Melita of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, the wife of Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich, who funded the developing NSDAP in the 1920s.

The history of the Russian Army in exile after their evacuation from the Crimea brought about the creation of three important and influential groups: the Russian All-Military Union (ROVS, founded in France in 1924); the predecessor of the People's Labor Union (NTS, founded Bulgaria in 1930); and the Brotherhood of Russian Truth (BRP, founded in Berlin in 1922). All of these organizations were closely interlinked, and often people belonged simultaneously to several of these structures.

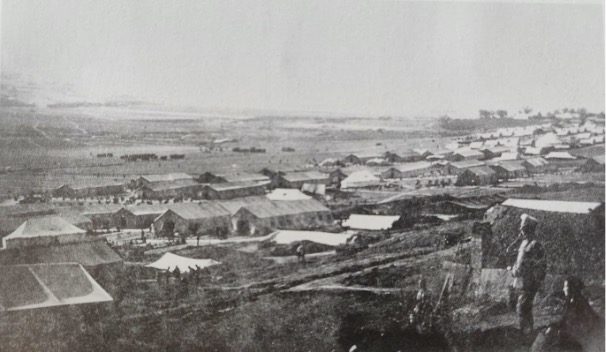

The Gallipoli camp (1920-1921)

Source

Source

Evacuation from Crimea on the Kherson ship (1920)

Source

Source

Ross, Nicolas. Kutepov. Pernik coal mine, Bulgaria.

Source

Source

From the Russian Army to Underground Organizations:

The Trajectory of the Whites in the European and French matrix

The Trajectory of the Whites in the European and French matrix

Content Oriented Web

Make great presentations, longreads, and landing pages, as well as photo stories, blogs, lookbooks, and all other kinds of content oriented projects.

Content Oriented Web

Make great presentations, longreads, and landing pages, as well as photo stories, blogs, lookbooks, and all other kinds of content oriented projects.

Content Oriented Web

Make great presentations, longreads, and landing pages, as well as photo stories, blogs, lookbooks, and all other kinds of content oriented projects.

[1] Paul Robinson, “The White Russian army in exile, 1920–1941” (PhD diss, University of Oxford, 1999), 28.

[2] Robinson, 29.

[3] Including, the Russian military and civilian ships taken from the Crimea, as well as various kinds of exported property, such as manufactured goods, artillery cargoes, coal, etc.

[4] Vladisvlav Ivanovich Goldin, Soldaty na chuzhbine. Russian All-Military Union, Russia and the Russian Diaspora in the XX-XXI centuries. (Arkhangelsk: Solti, 2006).

[5] On arrival at Constantinople, one of Wrangel’s first acts was to disband many rear and staff institutions that were no longer required. The army was left with three corps: the Don Cossack Corps, with 23,000 men under General Abramov; the Kuban Cossack Corps, with 12,000 men under General Fostikov; and the First Army Corps (which contained all the non-Cossack troops of the army), with 29,000 men under Kutepov.

[6] Robinson, 31–32.

[7] Robinson, iv.

[8] Robinson, 27.

[9] Robinson, 49.

[10] Robinson, v.

[11] A detachment of 2,000 men stayed at Gallipoli.

[12] Robinson, 47.

[13] The Yugoslav government provided the Russian émigrés with large sums of money out of its annual state budget, which were distributed by a body known as the “Derzhavnaia Kommissiia.” This gave aid to the sick and unemployed, helped provide retraining and find employment, and funded Russian schools. Among the latter were three Cadet Corps that had accompanied the Russian Army into exile (the Russian Cadet Corps, the Don Cossack Alexander III Cadet Corps, and the Crimean Cadet Corps). Robinson, 103–104. After further talks, Wrangel's military representative in Belgrade, Dmitry Nikolayevich Pototsky (1880–1949) persuaded the Yugoslavs to take an additional 4,000 men to carry out road-building projects. Robinson, 45.

[14] During negotiations in 1921, the Yugoslav government was persuaded to employ members of the same military unit on the same project, ensuring that units were kept together. As a result, the Cavalry Division of the First Army Corps, the Life Guards Don Battalion, and the Kuban Guards Regiment (in all some 5,000 men) joined the Yugoslav border service.

[15] As a result, 100 men of the First Army Corps left Gallipoli for Czechoslovakia on October 26, 1921 to attend Czechoslovak universities. RWR, 99–100. Once they arrived, they formed a group of “student-Gallipoliitsy” through whom contacts were maintained with the Russian Army. Later, veterans of the Russian Army established various other student organizations, such as the Society of Russian Students at Pfibram, which, in 1927, joined the ROVS. A larger group was the Gallipoliiskoe Zemliachestvo, founded in 1923. Robinson, 100–101.

[16] Robinson, 46.

[17] Robinson, 87.

[18] Ferdinand is the great-grandson of Francis, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld (1750–1806) and Victoria, his great‑great-granddaughter.

[2] Robinson, 29.

[3] Including, the Russian military and civilian ships taken from the Crimea, as well as various kinds of exported property, such as manufactured goods, artillery cargoes, coal, etc.

[4] Vladisvlav Ivanovich Goldin, Soldaty na chuzhbine. Russian All-Military Union, Russia and the Russian Diaspora in the XX-XXI centuries. (Arkhangelsk: Solti, 2006).

[5] On arrival at Constantinople, one of Wrangel’s first acts was to disband many rear and staff institutions that were no longer required. The army was left with three corps: the Don Cossack Corps, with 23,000 men under General Abramov; the Kuban Cossack Corps, with 12,000 men under General Fostikov; and the First Army Corps (which contained all the non-Cossack troops of the army), with 29,000 men under Kutepov.

[6] Robinson, 31–32.

[7] Robinson, iv.

[8] Robinson, 27.

[9] Robinson, 49.

[10] Robinson, v.

[11] A detachment of 2,000 men stayed at Gallipoli.

[12] Robinson, 47.

[13] The Yugoslav government provided the Russian émigrés with large sums of money out of its annual state budget, which were distributed by a body known as the “Derzhavnaia Kommissiia.” This gave aid to the sick and unemployed, helped provide retraining and find employment, and funded Russian schools. Among the latter were three Cadet Corps that had accompanied the Russian Army into exile (the Russian Cadet Corps, the Don Cossack Alexander III Cadet Corps, and the Crimean Cadet Corps). Robinson, 103–104. After further talks, Wrangel's military representative in Belgrade, Dmitry Nikolayevich Pototsky (1880–1949) persuaded the Yugoslavs to take an additional 4,000 men to carry out road-building projects. Robinson, 45.

[14] During negotiations in 1921, the Yugoslav government was persuaded to employ members of the same military unit on the same project, ensuring that units were kept together. As a result, the Cavalry Division of the First Army Corps, the Life Guards Don Battalion, and the Kuban Guards Regiment (in all some 5,000 men) joined the Yugoslav border service.

[15] As a result, 100 men of the First Army Corps left Gallipoli for Czechoslovakia on October 26, 1921 to attend Czechoslovak universities. RWR, 99–100. Once they arrived, they formed a group of “student-Gallipoliitsy” through whom contacts were maintained with the Russian Army. Later, veterans of the Russian Army established various other student organizations, such as the Society of Russian Students at Pfibram, which, in 1927, joined the ROVS. A larger group was the Gallipoliiskoe Zemliachestvo, founded in 1923. Robinson, 100–101.

[16] Robinson, 46.

[17] Robinson, 87.

[18] Ferdinand is the great-grandson of Francis, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld (1750–1806) and Victoria, his great‑great-granddaughter.