CHAPTER 1: U.S. INTELLIGENCE AND THE WHITES

Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War

This chapter describes the early collaboration between U.S. intelligence and White forces in their common fight against the Bolsheviks, which startedtowards the end of the short-lived Provisional Government of Alexandr Kerenskii in 1917. When the Russian Civil War was lost by the White-Entente alliance, the U.S. supported White émigrés that had settled in the West, particularly in Germany and France, the centers of White emigration in the interwar period. To that effect, the U.S. predominantly extended aid to staunchly Orthodox émigré figures, since they saw godless Bolshevism as an assault on Christian supremacy. Furthermore , the U.S. continued to liaise with representatives of the repressed Russian Orthodox Church inside Russia, which it saw as an important ally in the fight against the atheist Soviet Union from within.

Volunteer Army

To that end, with the outbreak of the Civil War, Poole embarked on a secret mission to South Russia lasting from December 1917 to January 1918 to liaise and coordinate with leaders of the White forces that fought against the rising Red Army: first to Rostov and then to Novocherkassk.

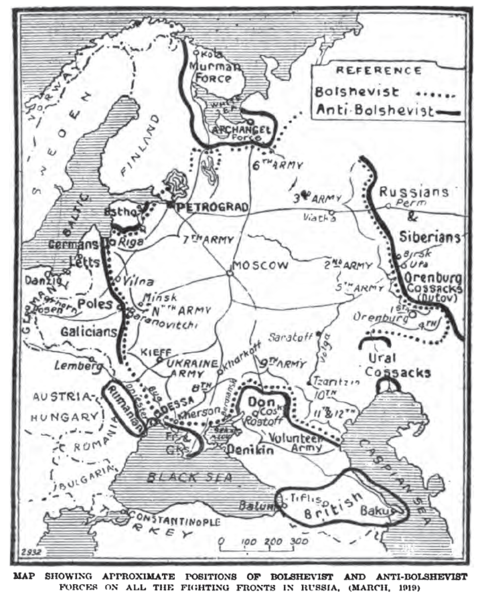

Starting in late 1917, the Western Allies began to back the White armies forming on four fronts to crush the bourgeoning Soviet Union: in the South Cossack forces gathered around the generals Anton Denikin and later Pyotr Wrangel; in the Northwest (Baltics) around General Nikolai Yudenich; in the North (Arkhangelsk) around General Miller; and in the East (Siberia) around Admiral Alexander Kolchak.

Collaboration with the Whites had its blessing from Lansing, who on December 10, “wrote a five-page brief for Wilson that presented the case for sending assistance to the White forces in southern Russia.”⁵⁹ Later that month, Wilson decided to covertly aid the Whites in the Don and Caucasus region. Since they were neither a recognized belligerent party nor a government, it was resolved to provide the funds covertly via the British.⁶⁰

Poole met the Cossack leader and the State Department’s “man of the hour” Alexei Kaledin (1861–February 1918), a cavalry general who led the Don Cossack Whites in the opening stages of the Russian Civil War, before Kaledin committed suicide a mere three months later.⁶¹

Kaledin had been singled out by Lansing as a capable future military dictator, once Bolshevik Russia was crushed. “Hailing the ‘victory of Kaledin and loyal troops,’ Consul General Summers suggested to Washington that the White forces might ‘liquidate the Bolshevik movement more quickly than expected.’”⁶²

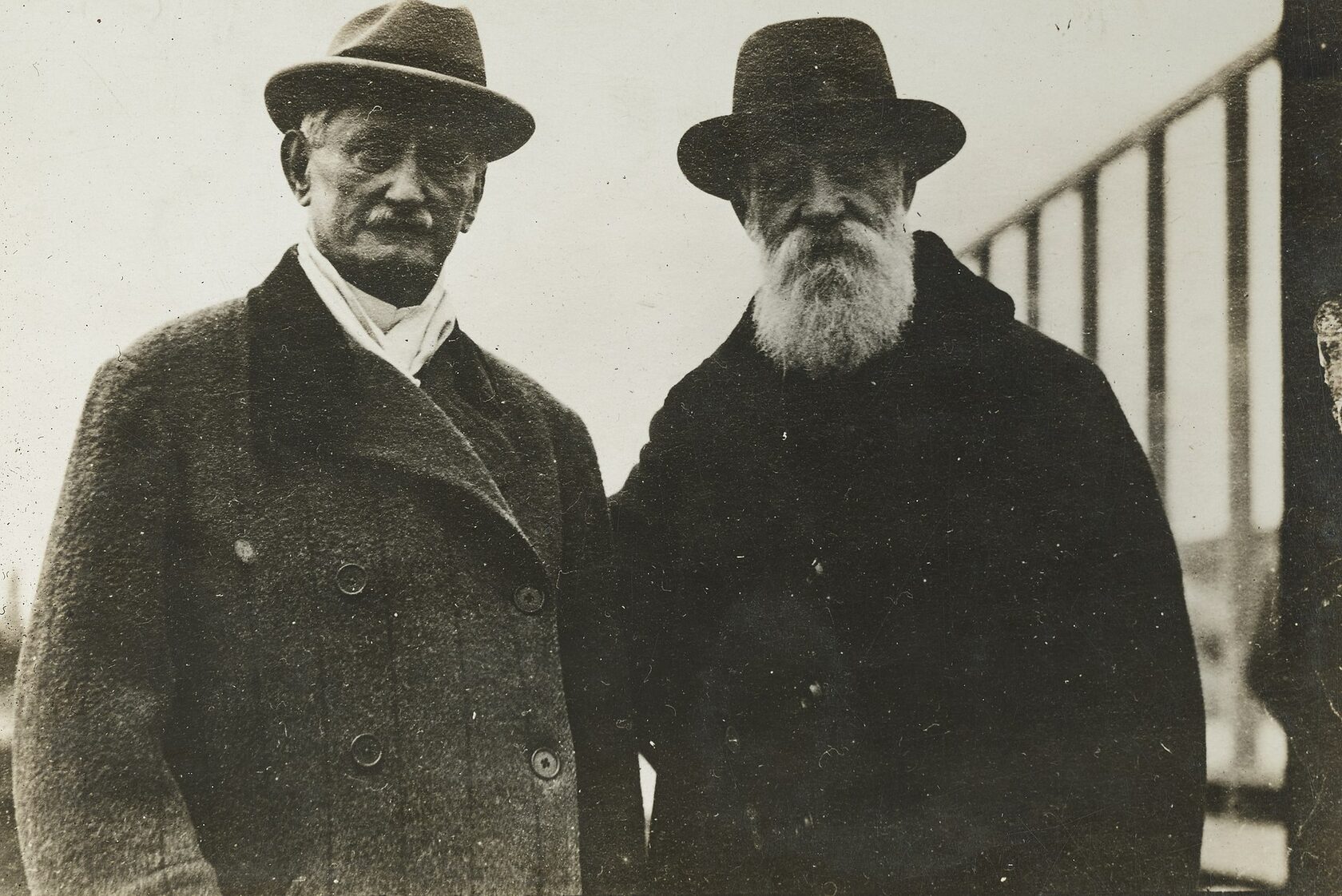

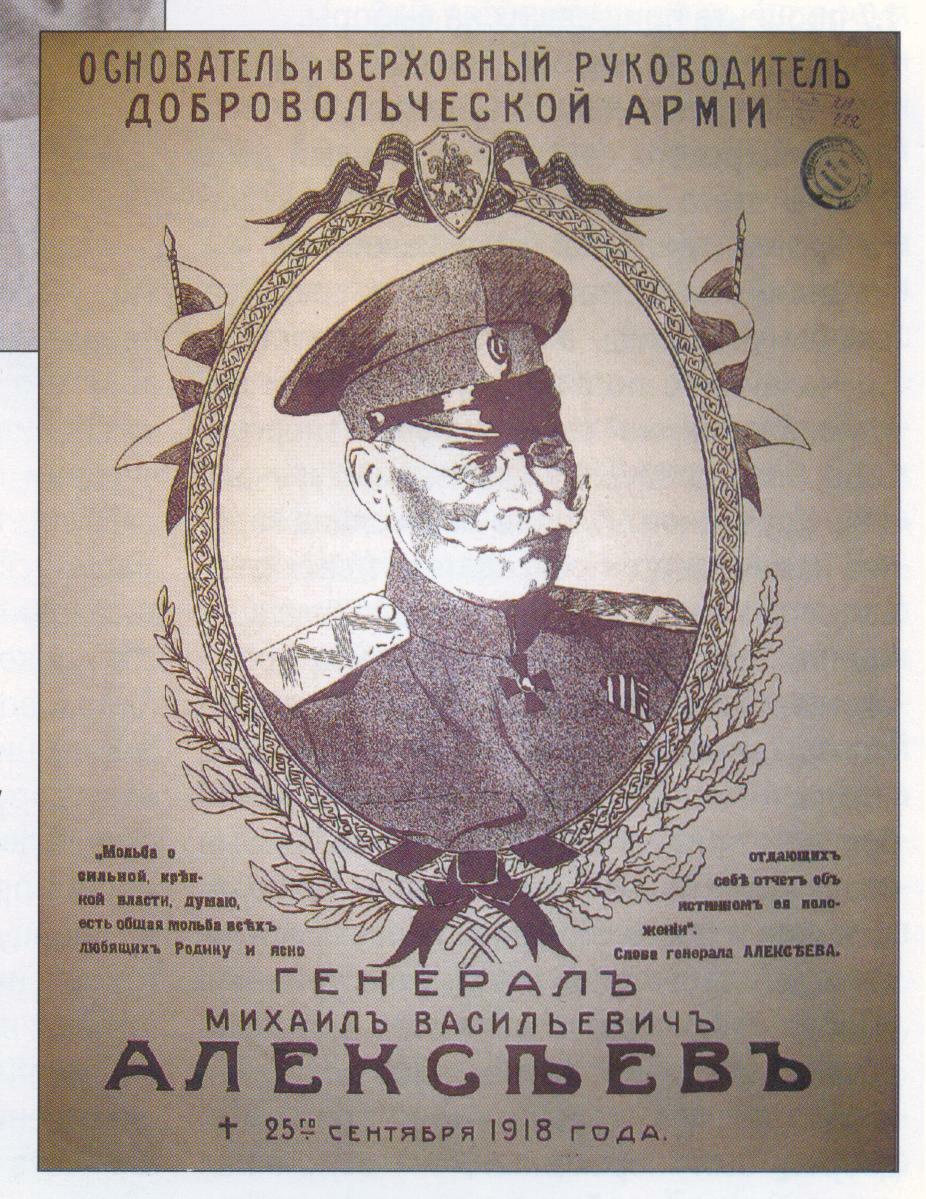

Kaledin had joined the bourgeoning 3,000–4,000 strong Volunteer Army, which had begun forming with British and French support in November/December 1917 in Novocherkassk under the fugitive coup leader, General Lavr Kornilov, and General Mikhail Alekseev (1857–October 1918). The latter, doubling as liaison for White finances, also conversed with Poole, who was coordinating with British and French military liaisons. According to Foglesong.⁶³

… Poole read his reports to Alekseev and showed copies to a French Colonel Hucher and the British General de Candolle. After all approved, Poole sent them to Summers and the State Department. When word came a few days later that the French government was prepared to provide 100 million rubles, Poole joined Hucher in giving Alekseev the good news.

In December 1917, Poole reported to Washington: the “projected armies will be a mobile police force,” against the Bolsheviks to “bring about the restoration of order in those portions of Russia which are not at the moment occupied by German troops or German organized units of Bolsheviks and released German prisoners.”⁶⁴ Although Poole reported, “From a military point of view, the position of the Don government is lamentably weak,” he nonetheless “recommended financial assistance to these forces.”⁶⁵

It was during Poole’s trip South, on January 9, 1918, that the creation of the Volunteer Army was officially announced: with Alekseev as leader; Kornilov as Commander-in-chief; General Alexander Lukomsky as Chief of Staff; General Anton Denikin as commander of the 1st Division and General Sergey Markov as commander of the 1st Officers regiment. A “Special Council” was established at the headquarters, which included prominent anti-Bolshevik figures such as Peter Struve, Pavel Miliukov, Mikhail Rodzianko, Sergey Sazonov and Boris Savinkov, some of whose names will reappear as important actors in subsequent U.S. collaborations with the Whites.

Most of the U.S.’s White contacts were former high-ranking czarist officers of the Imperial Army, who largely knew each other as alumni of elite military academies, such as the Nikolaev Military Academy (Nikolaev Academy of the General Staff) (1832–1918), including Anton Denikin, Lavr Kornilov, Pyotr Wrangel and Nikolai Yudenich.

Anton Denikin

The Volunteer Army remained active in South Russia during the Russian Civil War from 1917 to 1920 and fought against Bolshevik forces in the Southern Front and the Ukrainian War of Independence, until it was finally defeated by the Red Army. With U.S. support, its deployment resulted in a phase of brutal terror, as best exemplified by Anton Denikin (1872–1947), the gruesome Volunteer Army general who would become a future hero among White exiles, as reported in an account:⁶⁶

Denikin’s ferocity is notorious. A report of an American Red Cross man, who visited his camp, tells of thirty human heads seen projecting above the ground. The men had been killed by being buried alive—a form of atrocity too well known in the East—in which death is hastened by stones hurled at the protruding heads.

Starting in February 1918, the Volunteer Army of Generals Alexeev and Kornilov launched from the Don towards the Caucasus on the so-called “ice campaign” and were joined by several other White units that had formed among Cossacks from the Don, Kuban and Terek regions.⁶⁷ With increased material support from the U.S., Great Britain and France, in the autumn of 1918, a new White army formed around the first nucleus of the Volunteer Army, the so-called Armed Forces of Southern Russia (AFSR),commanded by General Denikin. ⁶⁸

In late 1918 and early 1919, Denikin defeated the 11th Soviet Army and captured the North Caucasus region. In October 1919, the 1st corps of the Volunteer Army under the command of General Alexander Kutepov managed to capture Kharkov, Kursk and, finally, the city of Orel, close to Moscow. However, this was the extreme point of the Whites’s advance towards the capital, and, being pushed back by the much larger Red forces, the White regiments began to retreat south.⁶⁹ In March 1920, Denikin’s troops embarked at Novorossiysk for the Crimea, where they merged with the forces of General Pyotr Wrangel (1878–1928). Subsequently, Wrangel succeeded Denikin as head-of-state in the occupied territories and as Commander-in-Chief of the merged White armies, which were renamed the Russian Army (commonly known as Army of Wrangel).⁷⁰ Wrangel’s forces continued fighting until November 11, 1920, but upon their defeat, they were evacuated from the Crimea to Constantinople on November 16, 1920 with allied help.⁷¹

When Poole returned from overseeing the creation of the Volunteer Army in early 1918, support of the Whites became his prime objective. According to James Gatewood, “By January 26, Poole was in Petrograd where he made a detailed report of his findings to the Ambassador in which he recommended that the United States support the counter-revolutionary elements as a strong nationalist movement.” Ambassador Francis allegedly refused to endorse this.⁷² However, shortly afterwards, on February 27, 1918, Francis had to close the embassy in Petrograd⁷³ and flee the city from approaching German troops. He established a temporary embassy at Vologda, 350 miles East of Moscow.⁷⁴ From there, he joined the interventionist calls of General Consul Summers and Poole, the latter vociferously advocating for an American military intervention in Siberia, which, half a year later, would eventually materialize.⁷⁵

Francis was subsequently demoted to Chargé d’Affaires ad interim at the embassy in Moscow until he left Russia in late 1918, which automatically catapulted Poole to the top of the diplomatic ladder. Gatewood states:⁷⁶

With the removal of the American embassy to Vologda … the only authentically accredited American official in Moscow with access to the Soviet government was Consul De Witte Clinton Poole. From February through July, Consul Poole’s alert reporting kept Washington and Vologda abreast of affairs in the Soviet capital.

In March 1918, Lenin decided the Bolsheviks would settle peacefully with the Central Powers at the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, while the Allies continued fighting until the Armistice of November 11, 1918. The peace treaty was certainly the last straw in the Allied decision for a military intervention against Bolshevik Russia. Although most U.S. diplomats, including the trio Francis, Summers and Poole, called for a military intervention,⁷⁷ it was not until July 1918 that the U.S. would decide to not only provide material and financial aid to Allied forces, but to send their own troops in support of the White regimes that had been sustained on the Russian periphery with Allied support.

Maddin Summers’s spy ring

On March 12, 1918, the Soviets transferred the center of the government to Moscow, which was less prone to being captured than Petrograd. In the final months that the U.S. Consulate in Moscow remained open (until August 1918), it was headed by Poole. On May 6, 1918, he succeeded U.S. Consul General Maddin Summers who had died unexpectedly.⁷⁸ With Summers’s death, Poole inherited his spy ring, “which at its height in the summer of 1918 numbered 30 sources in Moscow and various other Russian cities”⁷⁹ and was headed by the enigmatic Xenophon Dmitrievich de Blumenthal Kalamatiano. Since 1915, Kalamatiano had beenthe American representative of the Association of Commerce and Industry in Moscow, which had the ambitious goal to replace Germany as Russia’s biggest business partner. As Poole recalled, Kalamatiano’s espionage network was organized:⁸⁰

… on the well-known secret service system of cut-outs—that is, only two or three men were to know and have any contact with Kalamatiano. Then each of these men had two or three men in contact with him, and so on down, with the least possible crosscontacting.

According to Barnes Carr:⁸¹

Kal[amitiano] recruited dozens of assets, including the head of the Red Army’s communications office. Poole and Kalamatiano sent their reports to U.S. ambassador David Francis, a bourbon-sipping old Confederate who forwarded them to the State Department’s Bureau of Secret Intelligence, predecessor to the CIA and NSA.

It was on the night of July 16–17, 1918, that the Russian imperial family was clandestinely executed in Yekaterinburg. That same month, British and French intelligence planned another coup in Moscow which foresaw the assassination of the Bolshevik leadership, including Lenin. The unsuccessful plot involved, among others, the British agents Bruce Lockhart and Sidney Reilly, as well as the notorious terrorist Boris Savinkov ⁸² — a fact long rumored but only fairly recently supported by evidence.⁸³

After the failed assassination of Lenin by Fanny Kaplan on August 30 and as a consequence of the growing rumors of foreign plots, the Bolsheviks proceeded to shut down the British and U.S. embassies. With a U.S. military intervention on the horizon, their clandestine support of the Whites subsequently brought Poole, Francis and their diplomatic corps into a bind of their own making. They were now afraid that they would be held hostage by Bolsheviks before they could safely exit the turmoil, before the final closure of the U.S. embassy in August 1918.⁸⁴ According to Gatewood:⁸⁵

Feeling that the time had come to leave, Poole destroyed his codes and archives and placed the Consulate under Swedish care while he arranged for exit via Finland. … All of the American residents remaining in the city except Consul Poole and Allen Wardwell and J. W. Andrews of the Red Cross Mission, obtained clearance from the Russian authorities and embarked for Finland aboard a special train on the night of August 26–27. … It was not until September 19 that Poole finally reached Finland, the last American government official to leave Communist Russia.

Francis had left Vologda on July 24, 1918 and went to Arkhangelsk, where a White regime was forming; however, he left Russia altogether on November 7, 1918. The embassy was closed for ten months afterwards on September 14, 1919, and diplomatic relations between the U.S. and the Soviet Union were not resumed officially until November 16, 1933, the year Hitler took power in Germany.⁸⁶

In the same month as the plot to kill Lenin and the assassination of the czarist family, July 1918, the U.S. decided to join the Allied military interventions underway and to send reinforcement to the tens of thousands of troops from over a dozen countries that had already been deployed to crush the Soviet Union on four fronts. Thus, the U.S. quickly switched its allegiance, when starting to systematically support the remainder of the White forces in the Russian periphery who had been fighting with the Germans against the Red Army. Naturally, Poole would serve as chargé d’affaires to the White Provisional Government of the Northern Region in exile (November 1918 to June 1919).

As part of the North Russia intervention (March 1918–October 1919) and the Siberian intervention (August 1918–July 1920), around 11,000 U.S. troops joined the allied forces in Arkhangelsk in the North and Vladivostok in the East, where they were backing the establishment of White regimes. The goals of these interventions were partly to obtain key Russian resources and infrastructures while fighting the Central Powers as well as the Bolshevik government and also to consolidate the contacts with the Whites for future subversion.

North Russia intervention

Before U.S. troops landed in Arkhangelsk on August 2, 1918, anti-Bolshevik forces led by the czarist Captain Georgi Chaplin, with Allied support, had staged a coup against the local Soviet government. British diplomats had traveled to the city in preparation of the invasion, and Lieutenant General Frederick C. Poole [as to the knowledge of the author no relation to De Witt Clinton Poole who also spent some time in Arkhangelsk], who had been appointed by the British Secretary of State for War, Lord Milner, to lead the expedition to Arkhangelsk,⁸⁷ coordinated the coup with Chaplin. According to Clifford Kinvig, “The coup arrangements were agreed with [Frederick] Poole during July and were well coordinated with the Allied diplomats at Vologda.”⁸⁸ When Allied troops sailed into the port from the White Sea, they were met with little resistance and soon occupied the city.⁸⁹ Subsequently, the short-lived Supreme Administration of the Northern Region (August 2, 1918–September 27, 1918) was established by Chaplin and the anti-Bolshevik revolutionary Nikolai Tchaikovskii (1851–1926) and staffed, for the most part, with former politicians of the left-wing anti-Bolshevik opposition, such as the Socialist Revolutionary Party. But de facto General Poole led the show in Arkhangelsk, declaring martial law and introducing the death penalty on “false rumours calculated to provoke unrest or disturbance among the troops and population.”⁹⁰

The 4,500 American troops deployed to Arkhangelsk were under British command and were soon joined by a diplomatic corps that had evacuated from Soviet Russia. On September 6, a conference of diplomats, under the auspices of Ambassador Francis, condemned the type of leadership put in place and announced the removal of Chaplin and consorts from power, replacing it with a more White-aligned military regime. On September 27, 1918, members of the Supreme Directorate of the Northern Region finally resigned, and on October 9, the Provisional Government of the Northern Region (October 9, 1918–February 18, 1920) was formed, with anarchist Nikolai Tchaikovsky as chairman and Yevgenii Miller (1867–1939) as chief administrator. Miller would come to play a vital role in the Russian All-Military Union in the interwar period. The Miller-Tchaikovsky government ruled with an iron fist. To deal with its opposition, it established concentration camps on the islands of Mudyug, Iokanga and Solovetsky with untenable conditions, where many starved to death. About 52,000 people passed through the prisons, concentration camps, and labor camps of the Provisional Government of the Northern Region, and about 4,000 people were shot by the verdicts of the military courts.⁹¹

According to Gatewood:⁹²

By the time that American forces had reached Archangel, Ambassador Francis had become the most vociferous supporter of American aid to Anti-Bolshevik elements in Russia. The Ambassador was firmly convinced that the Bolsheviks and Germans were identical and should both be destroyed. A month before the Armistice was signed, Francis cabled the State Department requesting that 50,000 or 100,000 Allied troops be sent to Archangel to launch an offensive aimed at capturing Moscow and Petrograd from the Bolsheviks.

However, Francis’s plea remained wishful thinking, since Allied efforts were severely hampered by divided objectives and war-weariness. That the mission was an utter failure in military and moral terms is revealed in many accounts from the time.

As Gatewood states, and others on the ground confirm, the morale problem was largely rooted in the fact that the U.S. troops were not informed about the real purposes of their mission, that is to secure resources and to aid the Whites:⁹³

The American command’s most difficult problem in Russia was not relations with its Allies nor the sporadic clashes with the Bolsheviks. Rather it was in maintaining American morale. … Generally, both the troops and their leaders were confused about the Allied purposes in intervening in Russia. … Consul Poole, who became Chargé d’affaires at Archangel after he left Moscow, requested a firm statement of policy by the United States concerning the Archangel expedition because American troops were becoming suspicious of their continued presence in Russia. Poole recommended that the troops be retained to protect Russians who had cooperated with the intervention forces from retribution at the hands of the Bolsheviks. After news of the Armistice reached the troops at Archangel, Poole attempted to boost morale in a 1918 Thanksgiving speech to the men. He told them, not quite accurately, that they were protecting the one spot in Russia free from the Bolshevik curse. When one of the soldiers asked why they were still in Russia after the Armistice, Poole replied feebly that “President Wilson has thought of you and in good time will tell you and the rest of us what he expects each to do in order to hold steady the light of our forward-looking democracy.”

The North Russian Intervention proved extremely unpopular among the war-weary populace of the Allied countries, particularly after the Armistice of November 1918. Unable to hold the flanks in April 1919, along with mutinies in the ranks of the White forces, caused the Allied Powers to leave. The White Russian Northern Army was left to face the Red Army alone, and it quickly collapsed when the Bolsheviks launched a counter-offensive in December 1919. Many soldiers capitulated, and the remnants of the Army were evacuated from Arkhangelsk in February 1920, shortly before the Bolsheviks entered the city. The White Provisional Government of the Northern Region ceased to exist. White commander Yevgeny Miller carried on to the end with a number of other White officers including Grigory Chaplin, but had to flee at the last minute with an icebreaker when the Red army entered Arkhangelsk in February 1920.⁹⁴

Siberian Intervention & Admiral Alexander Kolchak

The Siberian Intervention was another Allied effort to crush the bourgeoning Soviet Union with the help of the Whites; this time from the East. The purpose of the Siberian intervention, supported by the American Expeditionary Force Siberia under the command of Major General William S. Graves, was mainly to assist the continued operation of the Trans-Siberian railroad and to protect American-supplied property. Totaling up to 8,763 men, the troops were quickly assigned guard duty along segments of the railway between Vladivostok and Nikolsk-Ussuriski in the north.⁹⁵ To that end, the Russian Railway Service Corps was created with U.S. personnel.⁹⁶

The first 3,000 American troops disembarked in Vladivostok between August 15 and August 21, 1918, followed by General Graves on September 4, 1918. The allied interventions had already started by then with the support of the Czechoslovak Legion, which was securing supplies of munitions and armaments in Russian ports. Coinciding with the March Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, Lenin had personally pledged that if the Czechoslovak Legion would stay neutral and leave Russia, they would enjoy safe passage through Siberia on their way to join the Allied forces on the Western Front. However, as the 50,000 Legion members made their way to Vladivostok along the Trans-Siberian Railroad, only half had arrived before the agreement broke down; fighting with the Bolsheviks ensued in May 1918.

Between 1918 and 1920 the Czechoslovak Legion at times controlled the Trans-Siberian Railway and several major cities in Siberia with the goal of supplying and assisting the Whites’ fight against the Red Army. It was in the course of the disastrous U.S. Siberia mission that American military leaders came in contact with, and started supporting, the bloody warlord Admiral Alexandr Kolchak (1874–1920), most of them concurring that “he was the last hope to save Eastern Russia from the scourge of Communism.”⁹⁷

U.S. support of Kolchak is unambiguous, with Foglesong stating that “In the case of Kolchak the U.S. government had approved the Embassy aiding him, hoping that his faction would gather to itself the Russian people.”⁹⁸ Regarding Kolchak’s brutality Commander Graves noted: “I doubt if history will show any country in the world during the last fifty years where murder could be committed so safely and with less danger of punishment than in Siberia during the regime of Admiral Kolchak.”⁹⁹ Following the Bolshevik revolution, Kolchak fled to Japan, where, in December 1917, he visited the British embassy in Tokyo and offered his services unconditionally and in whatever capacity at the disposal of His Majesty’s Government.¹⁰⁰

His offer was referred up to the Foreign Secretary, Arthur Balfour, and accepted shortly thereafter. Kolchak was instructed to join the British military mission in Baghdad. However, when he reached Singapore, he was ordered to turn back and go via Shanghai and Beijing to Harbin to command the Russian troops guarding the Russian-owned Chinese Eastern Railway in Manchuria, which the British government had decided could be a base for overthrowing the Bolsheviks and getting Russia back into the war with Germany.¹⁰¹

Kolchak’s arrival in Omsk, Siberia, was followed by a coup d’état on November 18, 1918, which ended the short-lived anti-Bolshevik Provisional All-Russian Government (September 23, 1918–November 18, 1918), replacing it with a more right-wing dictatorial regime—with the tacit support by the British. The Socialist-Revolutionary (SR) directory leader and members were arrested by Cossack troops and were subsequently expelled from Siberia, most of them ending up in Europe. The remaining cabinet members voted for Kolchak to become the head of government with emergency powers. He was named Supreme Ruler (Verkhovnyi Pravitel) and commander of the White movement, and later was largely recognized as such by the other White regimes that had emerged.¹⁰² Meanwhile, Kolchak established the anti-Bolshevik Russian Government with headquarters in Omsk, which operated until January 4, 1920.

Initially Kolchak’s forces had some military successes; however, from 1919 onwards, when the Red Army managed to reorganize and turn the attack against the Whites, they quickly lost ground. With local opponents beginning to agitate, international support starting to wane and the British turning more towards Denikin, Omsk was evacuated on November 14, 1919 The Red Army took the city without much resistance, capturing large amounts of ammunition and almost 50,000 soldiers. Kolchak fell into the hands of his enemies and was killed on February 6, 1920

Northwestern Government and Army

Besides the ones in the North, East and South, the Allied Powers installed a fourth White

government in the Northwest of Russia, i.e., the Baltics. Although the Treaty of Versailles

anticipated the German army would withdraw, only a small portion of the Freikorps still fighting in the Baltics actually retired. The rest continued fighting there, now with the support from the Western Allies, notably under the banner of the Northwestern Army.

The Northwestern Army originated from a White force that had been supported by the Germans and that had been formed, in spite of the Brest-Litovsk Treaty, in the summer of 1918 to fight against the Bolsheviks. By October 1918, a force of some 6,000 troops was created in the city of Pskov, called the Northern Corps. A quarter of them were officers of the former czarist army, and the rest was made up of local recruits, escaped Petrograd officers and POWs released by the Germans.

When military supplies promised by Germany did not materialize, the Estonian government, faced with a Bolshevik advance, agreed to accept the Whites into its territory and give it supplies, in exchange for passing under its control. Under pressure from the British General Gough, who promised to arrange for Estonian and British military assistance for the attack on Petrograd, Nikolai N. Yudenich (1862–1933) formed a Government of the Northwestern Region of Russia on August 11, 1919, encompassing the Petrograd, Novgorod and Pskov Governorates, which officially recognized Estonian independence.¹⁰³

By then, U.S., British and French troops had already built up a stronghold in the provisional

capital of Kaunas, Lithuania: The American mission to the Baltic Provinces led by Lieutenant Colonel Warwick Greene, the British civilian mission led by Stephen Tallents, as well as a French military mission. In June, the Northern Corps, now renamed the Northwestern Army, and largely under British control, started a march on Petrograd. But the Bolsheviks mobilized their reserves and aligned 40,000 men against the Northwestern Army supported by two Estonian divisions. On August 1, the Bolsheviks launched a counter-attack that drove them back.

The Whites had lost on all fronts: in the Northwest, General Yudenich failed to take Petrograd in autumn 1919 On the northern front, General Miller ceased fighting and went into exile in February 1920 Shortly afterwards, Denikin’s and Wrangel’s forces in the South withdrew to Constantinople. In Siberia, the troops of Admiral Kolchak were also forced to retreat. The military failures of the White interventions on all fronts, together with the evacuation of the Czechoslovak Legion in September 1920, compelled the Allied powers to end their military interventions, although the Japanese intervention in Siberia continued until 1922, and, until 1925, Japan continued to occupy the northern half of Sakhalin.

To that end, with the outbreak of the Civil War, Poole embarked on a secret mission to South Russia lasting from December 1917 to January 1918 to liaise and coordinate with leaders of the White forces that fought against the rising Red Army: first to Rostov and then to Novocherkassk.

Starting in late 1917, the Western Allies began to back the White armies forming on four fronts to crush the bourgeoning Soviet Union: in the South Cossack forces gathered around the generals Anton Denikin and later Pyotr Wrangel; in the Northwest (Baltics) around General Nikolai Yudenich; in the North (Arkhangelsk) around General Miller; and in the East (Siberia) around Admiral Alexander Kolchak.

Collaboration with the Whites had its blessing from Lansing, who on December 10, “wrote a five-page brief for Wilson that presented the case for sending assistance to the White forces in southern Russia.”⁵⁹ Later that month, Wilson decided to covertly aid the Whites in the Don and Caucasus region. Since they were neither a recognized belligerent party nor a government, it was resolved to provide the funds covertly via the British.⁶⁰

Poole met the Cossack leader and the State Department’s “man of the hour” Alexei Kaledin (1861–February 1918), a cavalry general who led the Don Cossack Whites in the opening stages of the Russian Civil War, before Kaledin committed suicide a mere three months later.⁶¹

Kaledin had been singled out by Lansing as a capable future military dictator, once Bolshevik Russia was crushed. “Hailing the ‘victory of Kaledin and loyal troops,’ Consul General Summers suggested to Washington that the White forces might ‘liquidate the Bolshevik movement more quickly than expected.’”⁶²

Kaledin had joined the bourgeoning 3,000–4,000 strong Volunteer Army, which had begun forming with British and French support in November/December 1917 in Novocherkassk under the fugitive coup leader, General Lavr Kornilov, and General Mikhail Alekseev (1857–October 1918). The latter, doubling as liaison for White finances, also conversed with Poole, who was coordinating with British and French military liaisons. According to Foglesong.⁶³

… Poole read his reports to Alekseev and showed copies to a French Colonel Hucher and the British General de Candolle. After all approved, Poole sent them to Summers and the State Department. When word came a few days later that the French government was prepared to provide 100 million rubles, Poole joined Hucher in giving Alekseev the good news.

In December 1917, Poole reported to Washington: the “projected armies will be a mobile police force,” against the Bolsheviks to “bring about the restoration of order in those portions of Russia which are not at the moment occupied by German troops or German organized units of Bolsheviks and released German prisoners.”⁶⁴ Although Poole reported, “From a military point of view, the position of the Don government is lamentably weak,” he nonetheless “recommended financial assistance to these forces.”⁶⁵

It was during Poole’s trip South, on January 9, 1918, that the creation of the Volunteer Army was officially announced: with Alekseev as leader; Kornilov as Commander-in-chief; General Alexander Lukomsky as Chief of Staff; General Anton Denikin as commander of the 1st Division and General Sergey Markov as commander of the 1st Officers regiment. A “Special Council” was established at the headquarters, which included prominent anti-Bolshevik figures such as Peter Struve, Pavel Miliukov, Mikhail Rodzianko, Sergey Sazonov and Boris Savinkov, some of whose names will reappear as important actors in subsequent U.S. collaborations with the Whites.

Most of the U.S.’s White contacts were former high-ranking czarist officers of the Imperial Army, who largely knew each other as alumni of elite military academies, such as the Nikolaev Military Academy (Nikolaev Academy of the General Staff) (1832–1918), including Anton Denikin, Lavr Kornilov, Pyotr Wrangel and Nikolai Yudenich.

Anton Denikin

The Volunteer Army remained active in South Russia during the Russian Civil War from 1917 to 1920 and fought against Bolshevik forces in the Southern Front and the Ukrainian War of Independence, until it was finally defeated by the Red Army. With U.S. support, its deployment resulted in a phase of brutal terror, as best exemplified by Anton Denikin (1872–1947), the gruesome Volunteer Army general who would become a future hero among White exiles, as reported in an account:⁶⁶

Denikin’s ferocity is notorious. A report of an American Red Cross man, who visited his camp, tells of thirty human heads seen projecting above the ground. The men had been killed by being buried alive—a form of atrocity too well known in the East—in which death is hastened by stones hurled at the protruding heads.

Starting in February 1918, the Volunteer Army of Generals Alexeev and Kornilov launched from the Don towards the Caucasus on the so-called “ice campaign” and were joined by several other White units that had formed among Cossacks from the Don, Kuban and Terek regions.⁶⁷ With increased material support from the U.S., Great Britain and France, in the autumn of 1918, a new White army formed around the first nucleus of the Volunteer Army, the so-called Armed Forces of Southern Russia (AFSR),commanded by General Denikin. ⁶⁸

In late 1918 and early 1919, Denikin defeated the 11th Soviet Army and captured the North Caucasus region. In October 1919, the 1st corps of the Volunteer Army under the command of General Alexander Kutepov managed to capture Kharkov, Kursk and, finally, the city of Orel, close to Moscow. However, this was the extreme point of the Whites’s advance towards the capital, and, being pushed back by the much larger Red forces, the White regiments began to retreat south.⁶⁹ In March 1920, Denikin’s troops embarked at Novorossiysk for the Crimea, where they merged with the forces of General Pyotr Wrangel (1878–1928). Subsequently, Wrangel succeeded Denikin as head-of-state in the occupied territories and as Commander-in-Chief of the merged White armies, which were renamed the Russian Army (commonly known as Army of Wrangel).⁷⁰ Wrangel’s forces continued fighting until November 11, 1920, but upon their defeat, they were evacuated from the Crimea to Constantinople on November 16, 1920 with allied help.⁷¹

When Poole returned from overseeing the creation of the Volunteer Army in early 1918, support of the Whites became his prime objective. According to James Gatewood, “By January 26, Poole was in Petrograd where he made a detailed report of his findings to the Ambassador in which he recommended that the United States support the counter-revolutionary elements as a strong nationalist movement.” Ambassador Francis allegedly refused to endorse this.⁷² However, shortly afterwards, on February 27, 1918, Francis had to close the embassy in Petrograd⁷³ and flee the city from approaching German troops. He established a temporary embassy at Vologda, 350 miles East of Moscow.⁷⁴ From there, he joined the interventionist calls of General Consul Summers and Poole, the latter vociferously advocating for an American military intervention in Siberia, which, half a year later, would eventually materialize.⁷⁵

Francis was subsequently demoted to Chargé d’Affaires ad interim at the embassy in Moscow until he left Russia in late 1918, which automatically catapulted Poole to the top of the diplomatic ladder. Gatewood states:⁷⁶

With the removal of the American embassy to Vologda … the only authentically accredited American official in Moscow with access to the Soviet government was Consul De Witte Clinton Poole. From February through July, Consul Poole’s alert reporting kept Washington and Vologda abreast of affairs in the Soviet capital.

In March 1918, Lenin decided the Bolsheviks would settle peacefully with the Central Powers at the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, while the Allies continued fighting until the Armistice of November 11, 1918. The peace treaty was certainly the last straw in the Allied decision for a military intervention against Bolshevik Russia. Although most U.S. diplomats, including the trio Francis, Summers and Poole, called for a military intervention,⁷⁷ it was not until July 1918 that the U.S. would decide to not only provide material and financial aid to Allied forces, but to send their own troops in support of the White regimes that had been sustained on the Russian periphery with Allied support.

Maddin Summers’s spy ring

On March 12, 1918, the Soviets transferred the center of the government to Moscow, which was less prone to being captured than Petrograd. In the final months that the U.S. Consulate in Moscow remained open (until August 1918), it was headed by Poole. On May 6, 1918, he succeeded U.S. Consul General Maddin Summers who had died unexpectedly.⁷⁸ With Summers’s death, Poole inherited his spy ring, “which at its height in the summer of 1918 numbered 30 sources in Moscow and various other Russian cities”⁷⁹ and was headed by the enigmatic Xenophon Dmitrievich de Blumenthal Kalamatiano. Since 1915, Kalamatiano had beenthe American representative of the Association of Commerce and Industry in Moscow, which had the ambitious goal to replace Germany as Russia’s biggest business partner. As Poole recalled, Kalamatiano’s espionage network was organized:⁸⁰

… on the well-known secret service system of cut-outs—that is, only two or three men were to know and have any contact with Kalamatiano. Then each of these men had two or three men in contact with him, and so on down, with the least possible crosscontacting.

According to Barnes Carr:⁸¹

Kal[amitiano] recruited dozens of assets, including the head of the Red Army’s communications office. Poole and Kalamatiano sent their reports to U.S. ambassador David Francis, a bourbon-sipping old Confederate who forwarded them to the State Department’s Bureau of Secret Intelligence, predecessor to the CIA and NSA.

It was on the night of July 16–17, 1918, that the Russian imperial family was clandestinely executed in Yekaterinburg. That same month, British and French intelligence planned another coup in Moscow which foresaw the assassination of the Bolshevik leadership, including Lenin. The unsuccessful plot involved, among others, the British agents Bruce Lockhart and Sidney Reilly, as well as the notorious terrorist Boris Savinkov ⁸² — a fact long rumored but only fairly recently supported by evidence.⁸³

After the failed assassination of Lenin by Fanny Kaplan on August 30 and as a consequence of the growing rumors of foreign plots, the Bolsheviks proceeded to shut down the British and U.S. embassies. With a U.S. military intervention on the horizon, their clandestine support of the Whites subsequently brought Poole, Francis and their diplomatic corps into a bind of their own making. They were now afraid that they would be held hostage by Bolsheviks before they could safely exit the turmoil, before the final closure of the U.S. embassy in August 1918.⁸⁴ According to Gatewood:⁸⁵

Feeling that the time had come to leave, Poole destroyed his codes and archives and placed the Consulate under Swedish care while he arranged for exit via Finland. … All of the American residents remaining in the city except Consul Poole and Allen Wardwell and J. W. Andrews of the Red Cross Mission, obtained clearance from the Russian authorities and embarked for Finland aboard a special train on the night of August 26–27. … It was not until September 19 that Poole finally reached Finland, the last American government official to leave Communist Russia.

Francis had left Vologda on July 24, 1918 and went to Arkhangelsk, where a White regime was forming; however, he left Russia altogether on November 7, 1918. The embassy was closed for ten months afterwards on September 14, 1919, and diplomatic relations between the U.S. and the Soviet Union were not resumed officially until November 16, 1933, the year Hitler took power in Germany.⁸⁶

In the same month as the plot to kill Lenin and the assassination of the czarist family, July 1918, the U.S. decided to join the Allied military interventions underway and to send reinforcement to the tens of thousands of troops from over a dozen countries that had already been deployed to crush the Soviet Union on four fronts. Thus, the U.S. quickly switched its allegiance, when starting to systematically support the remainder of the White forces in the Russian periphery who had been fighting with the Germans against the Red Army. Naturally, Poole would serve as chargé d’affaires to the White Provisional Government of the Northern Region in exile (November 1918 to June 1919).

As part of the North Russia intervention (March 1918–October 1919) and the Siberian intervention (August 1918–July 1920), around 11,000 U.S. troops joined the allied forces in Arkhangelsk in the North and Vladivostok in the East, where they were backing the establishment of White regimes. The goals of these interventions were partly to obtain key Russian resources and infrastructures while fighting the Central Powers as well as the Bolshevik government and also to consolidate the contacts with the Whites for future subversion.

North Russia intervention

Before U.S. troops landed in Arkhangelsk on August 2, 1918, anti-Bolshevik forces led by the czarist Captain Georgi Chaplin, with Allied support, had staged a coup against the local Soviet government. British diplomats had traveled to the city in preparation of the invasion, and Lieutenant General Frederick C. Poole [as to the knowledge of the author no relation to De Witt Clinton Poole who also spent some time in Arkhangelsk], who had been appointed by the British Secretary of State for War, Lord Milner, to lead the expedition to Arkhangelsk,⁸⁷ coordinated the coup with Chaplin. According to Clifford Kinvig, “The coup arrangements were agreed with [Frederick] Poole during July and were well coordinated with the Allied diplomats at Vologda.”⁸⁸ When Allied troops sailed into the port from the White Sea, they were met with little resistance and soon occupied the city.⁸⁹ Subsequently, the short-lived Supreme Administration of the Northern Region (August 2, 1918–September 27, 1918) was established by Chaplin and the anti-Bolshevik revolutionary Nikolai Tchaikovskii (1851–1926) and staffed, for the most part, with former politicians of the left-wing anti-Bolshevik opposition, such as the Socialist Revolutionary Party. But de facto General Poole led the show in Arkhangelsk, declaring martial law and introducing the death penalty on “false rumours calculated to provoke unrest or disturbance among the troops and population.”⁹⁰

The 4,500 American troops deployed to Arkhangelsk were under British command and were soon joined by a diplomatic corps that had evacuated from Soviet Russia. On September 6, a conference of diplomats, under the auspices of Ambassador Francis, condemned the type of leadership put in place and announced the removal of Chaplin and consorts from power, replacing it with a more White-aligned military regime. On September 27, 1918, members of the Supreme Directorate of the Northern Region finally resigned, and on October 9, the Provisional Government of the Northern Region (October 9, 1918–February 18, 1920) was formed, with anarchist Nikolai Tchaikovsky as chairman and Yevgenii Miller (1867–1939) as chief administrator. Miller would come to play a vital role in the Russian All-Military Union in the interwar period. The Miller-Tchaikovsky government ruled with an iron fist. To deal with its opposition, it established concentration camps on the islands of Mudyug, Iokanga and Solovetsky with untenable conditions, where many starved to death. About 52,000 people passed through the prisons, concentration camps, and labor camps of the Provisional Government of the Northern Region, and about 4,000 people were shot by the verdicts of the military courts.⁹¹

According to Gatewood:⁹²

By the time that American forces had reached Archangel, Ambassador Francis had become the most vociferous supporter of American aid to Anti-Bolshevik elements in Russia. The Ambassador was firmly convinced that the Bolsheviks and Germans were identical and should both be destroyed. A month before the Armistice was signed, Francis cabled the State Department requesting that 50,000 or 100,000 Allied troops be sent to Archangel to launch an offensive aimed at capturing Moscow and Petrograd from the Bolsheviks.

However, Francis’s plea remained wishful thinking, since Allied efforts were severely hampered by divided objectives and war-weariness. That the mission was an utter failure in military and moral terms is revealed in many accounts from the time.

As Gatewood states, and others on the ground confirm, the morale problem was largely rooted in the fact that the U.S. troops were not informed about the real purposes of their mission, that is to secure resources and to aid the Whites:⁹³

The American command’s most difficult problem in Russia was not relations with its Allies nor the sporadic clashes with the Bolsheviks. Rather it was in maintaining American morale. … Generally, both the troops and their leaders were confused about the Allied purposes in intervening in Russia. … Consul Poole, who became Chargé d’affaires at Archangel after he left Moscow, requested a firm statement of policy by the United States concerning the Archangel expedition because American troops were becoming suspicious of their continued presence in Russia. Poole recommended that the troops be retained to protect Russians who had cooperated with the intervention forces from retribution at the hands of the Bolsheviks. After news of the Armistice reached the troops at Archangel, Poole attempted to boost morale in a 1918 Thanksgiving speech to the men. He told them, not quite accurately, that they were protecting the one spot in Russia free from the Bolshevik curse. When one of the soldiers asked why they were still in Russia after the Armistice, Poole replied feebly that “President Wilson has thought of you and in good time will tell you and the rest of us what he expects each to do in order to hold steady the light of our forward-looking democracy.”

The North Russian Intervention proved extremely unpopular among the war-weary populace of the Allied countries, particularly after the Armistice of November 1918. Unable to hold the flanks in April 1919, along with mutinies in the ranks of the White forces, caused the Allied Powers to leave. The White Russian Northern Army was left to face the Red Army alone, and it quickly collapsed when the Bolsheviks launched a counter-offensive in December 1919. Many soldiers capitulated, and the remnants of the Army were evacuated from Arkhangelsk in February 1920, shortly before the Bolsheviks entered the city. The White Provisional Government of the Northern Region ceased to exist. White commander Yevgeny Miller carried on to the end with a number of other White officers including Grigory Chaplin, but had to flee at the last minute with an icebreaker when the Red army entered Arkhangelsk in February 1920.⁹⁴

Siberian Intervention & Admiral Alexander Kolchak

The Siberian Intervention was another Allied effort to crush the bourgeoning Soviet Union with the help of the Whites; this time from the East. The purpose of the Siberian intervention, supported by the American Expeditionary Force Siberia under the command of Major General William S. Graves, was mainly to assist the continued operation of the Trans-Siberian railroad and to protect American-supplied property. Totaling up to 8,763 men, the troops were quickly assigned guard duty along segments of the railway between Vladivostok and Nikolsk-Ussuriski in the north.⁹⁵ To that end, the Russian Railway Service Corps was created with U.S. personnel.⁹⁶

The first 3,000 American troops disembarked in Vladivostok between August 15 and August 21, 1918, followed by General Graves on September 4, 1918. The allied interventions had already started by then with the support of the Czechoslovak Legion, which was securing supplies of munitions and armaments in Russian ports. Coinciding with the March Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, Lenin had personally pledged that if the Czechoslovak Legion would stay neutral and leave Russia, they would enjoy safe passage through Siberia on their way to join the Allied forces on the Western Front. However, as the 50,000 Legion members made their way to Vladivostok along the Trans-Siberian Railroad, only half had arrived before the agreement broke down; fighting with the Bolsheviks ensued in May 1918.

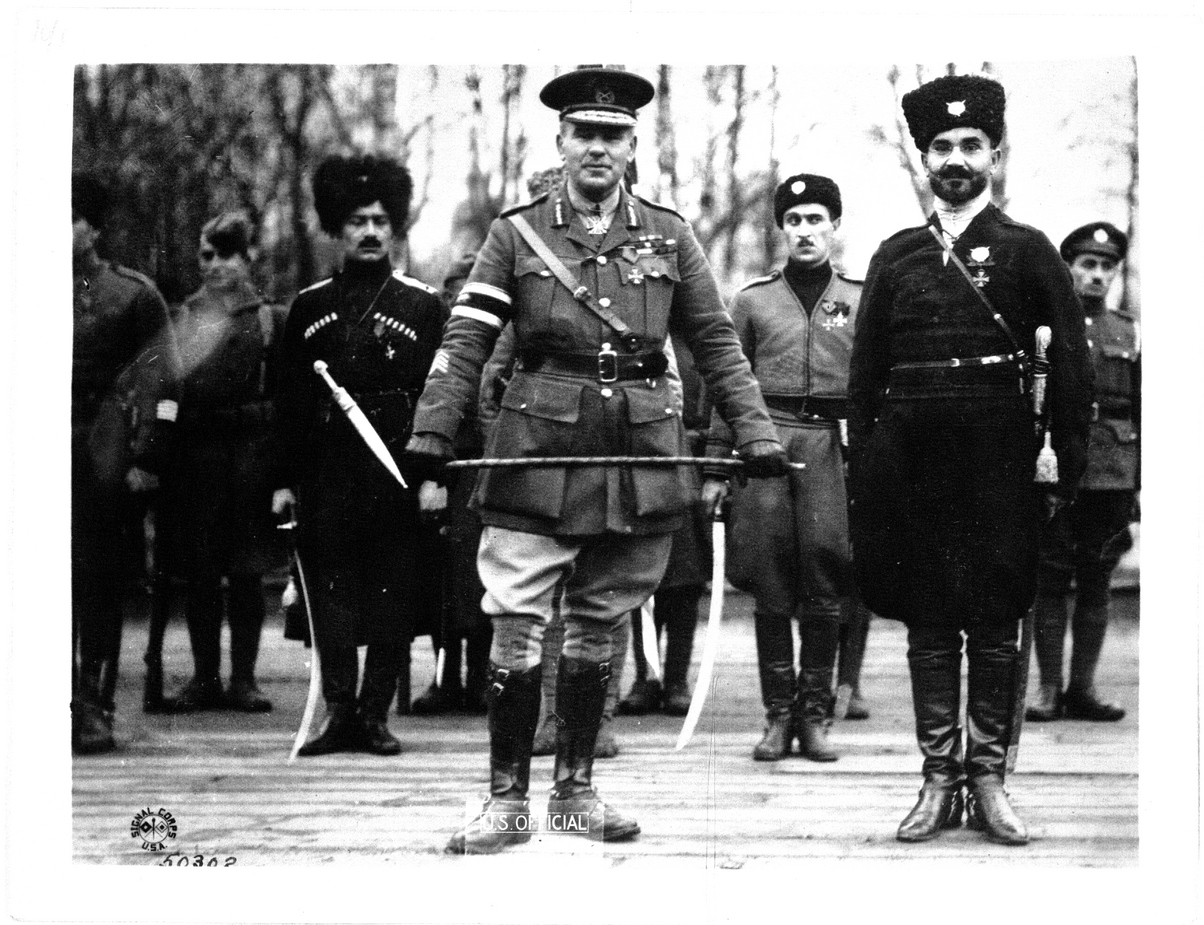

Between 1918 and 1920 the Czechoslovak Legion at times controlled the Trans-Siberian Railway and several major cities in Siberia with the goal of supplying and assisting the Whites’ fight against the Red Army. It was in the course of the disastrous U.S. Siberia mission that American military leaders came in contact with, and started supporting, the bloody warlord Admiral Alexandr Kolchak (1874–1920), most of them concurring that “he was the last hope to save Eastern Russia from the scourge of Communism.”⁹⁷

U.S. support of Kolchak is unambiguous, with Foglesong stating that “In the case of Kolchak the U.S. government had approved the Embassy aiding him, hoping that his faction would gather to itself the Russian people.”⁹⁸ Regarding Kolchak’s brutality Commander Graves noted: “I doubt if history will show any country in the world during the last fifty years where murder could be committed so safely and with less danger of punishment than in Siberia during the regime of Admiral Kolchak.”⁹⁹ Following the Bolshevik revolution, Kolchak fled to Japan, where, in December 1917, he visited the British embassy in Tokyo and offered his services unconditionally and in whatever capacity at the disposal of His Majesty’s Government.¹⁰⁰

His offer was referred up to the Foreign Secretary, Arthur Balfour, and accepted shortly thereafter. Kolchak was instructed to join the British military mission in Baghdad. However, when he reached Singapore, he was ordered to turn back and go via Shanghai and Beijing to Harbin to command the Russian troops guarding the Russian-owned Chinese Eastern Railway in Manchuria, which the British government had decided could be a base for overthrowing the Bolsheviks and getting Russia back into the war with Germany.¹⁰¹

Kolchak’s arrival in Omsk, Siberia, was followed by a coup d’état on November 18, 1918, which ended the short-lived anti-Bolshevik Provisional All-Russian Government (September 23, 1918–November 18, 1918), replacing it with a more right-wing dictatorial regime—with the tacit support by the British. The Socialist-Revolutionary (SR) directory leader and members were arrested by Cossack troops and were subsequently expelled from Siberia, most of them ending up in Europe. The remaining cabinet members voted for Kolchak to become the head of government with emergency powers. He was named Supreme Ruler (Verkhovnyi Pravitel) and commander of the White movement, and later was largely recognized as such by the other White regimes that had emerged.¹⁰² Meanwhile, Kolchak established the anti-Bolshevik Russian Government with headquarters in Omsk, which operated until January 4, 1920.

Initially Kolchak’s forces had some military successes; however, from 1919 onwards, when the Red Army managed to reorganize and turn the attack against the Whites, they quickly lost ground. With local opponents beginning to agitate, international support starting to wane and the British turning more towards Denikin, Omsk was evacuated on November 14, 1919 The Red Army took the city without much resistance, capturing large amounts of ammunition and almost 50,000 soldiers. Kolchak fell into the hands of his enemies and was killed on February 6, 1920

Northwestern Government and Army

Besides the ones in the North, East and South, the Allied Powers installed a fourth White

government in the Northwest of Russia, i.e., the Baltics. Although the Treaty of Versailles

anticipated the German army would withdraw, only a small portion of the Freikorps still fighting in the Baltics actually retired. The rest continued fighting there, now with the support from the Western Allies, notably under the banner of the Northwestern Army.

The Northwestern Army originated from a White force that had been supported by the Germans and that had been formed, in spite of the Brest-Litovsk Treaty, in the summer of 1918 to fight against the Bolsheviks. By October 1918, a force of some 6,000 troops was created in the city of Pskov, called the Northern Corps. A quarter of them were officers of the former czarist army, and the rest was made up of local recruits, escaped Petrograd officers and POWs released by the Germans.

When military supplies promised by Germany did not materialize, the Estonian government, faced with a Bolshevik advance, agreed to accept the Whites into its territory and give it supplies, in exchange for passing under its control. Under pressure from the British General Gough, who promised to arrange for Estonian and British military assistance for the attack on Petrograd, Nikolai N. Yudenich (1862–1933) formed a Government of the Northwestern Region of Russia on August 11, 1919, encompassing the Petrograd, Novgorod and Pskov Governorates, which officially recognized Estonian independence.¹⁰³

By then, U.S., British and French troops had already built up a stronghold in the provisional

capital of Kaunas, Lithuania: The American mission to the Baltic Provinces led by Lieutenant Colonel Warwick Greene, the British civilian mission led by Stephen Tallents, as well as a French military mission. In June, the Northern Corps, now renamed the Northwestern Army, and largely under British control, started a march on Petrograd. But the Bolsheviks mobilized their reserves and aligned 40,000 men against the Northwestern Army supported by two Estonian divisions. On August 1, the Bolsheviks launched a counter-attack that drove them back.

The Whites had lost on all fronts: in the Northwest, General Yudenich failed to take Petrograd in autumn 1919 On the northern front, General Miller ceased fighting and went into exile in February 1920 Shortly afterwards, Denikin’s and Wrangel’s forces in the South withdrew to Constantinople. In Siberia, the troops of Admiral Kolchak were also forced to retreat. The military failures of the White interventions on all fronts, together with the evacuation of the Czechoslovak Legion in September 1920, compelled the Allied powers to end their military interventions, although the Japanese intervention in Siberia continued until 1922, and, until 1925, Japan continued to occupy the northern half of Sakhalin.

Map of the positions of the Allied expeditionary forces and of the White Armies in Russia, 1919

Source

Source

Chapter Content

Allied intervention on the Russian Civil War

Government of South of Russia. Crimea, Sevastopol, 1920

Source

Source

Alexandr Kolchak with British General Alfred Knox,1919

Source

Source

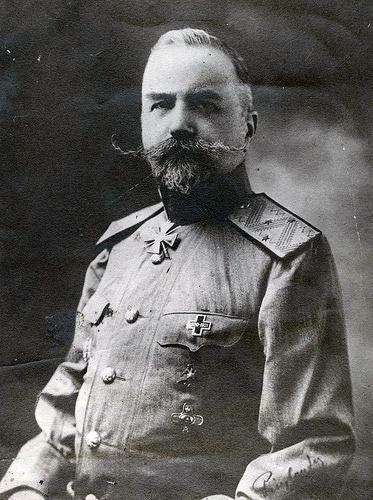

General Mikhail Alekseev (1857–1918)

Source

Source

Anton Ivanovich Denikin (1857–1918)

Source

Source

Australians in North Russia, 1919

Source

Source

General Frederick Poole in Arkhangelsk, October 1919

Source

Source

General Yevgenii Miller (1867–1939)

Source

Source

Czechoslovak Legion, 1918

Source

Source

Admiral Alexandr Kolchak (1874–1920)

Source

Source

The Staff of Northwestern Army with General Nikolai Yudenich

Source

Source

Explore the networks, citations, and documents using the buttons on the right

The Northwestern Army in Estonia,1919

Source

Source

Content Oriented Web

Make great presentations, longreads, and landing pages, as well as photo stories, blogs, lookbooks, and all other kinds of content oriented projects.

Content Oriented Web

Make great presentations, longreads, and landing pages, as well as photo stories, blogs, lookbooks, and all other kinds of content oriented projects.

Content Oriented Web

Make great presentations, longreads, and landing pages, as well as photo stories, blogs, lookbooks, and all other kinds of content oriented projects.

[59] Foglesong, America’s Secret War, 87.

[60] “… [in December 1917] President Wilson had authorized aid to anti-Bolshevik forces in the Don and Caucasus regions. Since the Wilson administration was unable to give official U.S. funds directly to groups that were neither recognized governments nor belligerents in the war against Germany, it was necessary to find indirect methods of financing. The administration therefore promised British leaders that it would reimburse them for support to the Whites. Over several months, from late 1917 through the spring of 1918, U.S. officials worked with British counterparts in efforts to transmit funds.” Foglesong, America’s Secret War, 77.

[61] Foglesong, America’s Secret War, 78 ff., 92–93.

[62] Foglesong, America’s Secret War, 92.

[63] Foglesong, America’s Secret War, 93.

[64] David R. Francis, “The Ambassador in Russia (Francis) to the Secretary of State,” No. 1036, Petrograd, January 24/February 6, 1918, Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, 1918, Russia, Volume II, File No. 861.00/1707 https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1918Russiav02/d732.

[65] Foglesong, America’s Secret War, 92–93.

[66] Joseph King, Three Bloody Men: Mannerheim, Denikin, Koltchak (Glasgow: Reformers Bookstall, July 1919), 6, http://russianrevolution.marx-memorial-library.org.uk/mml-three-bloody-men-by-joseph-king/.

[67] Nicolas Ross, De Koutiepov à Miller: le combat des russes blancs 1930–1940 (Editions des Syrtes, 2017), 7.

[68] Ross, De Koutiepov à Miller, 8.

[69] Ross, De Koutiepov à Miller, 8.

[70] Paul Robinson, The White Russian army in exile, 1920-1941 (PhD thesis, University of Oxford, 1999), 6–7.

[71] Ross, De Koutiepov à Miller, 9.

[72] James Gatewood, American Observers in the Soviet Union 1917-1933 (University of Wisconsin, 1968), 7. James Gatewood’s thesis extensively covers the scope of American presence during the revolutionary years in Russia and beyond, including many first-hand accounts.

[73] “Since he expected a quick return to Petrograd, Francis directed staff to take only records needed for current business. The staff burned the previous 10-year accumulation of sensitive files and left the remaining records in the care of the neutral Norwegians, who assumed responsibility for American interests in Petrograd. One vice consul remained in the city to gather information and to take care of consular business.” David A. Langbart, “‘No Little Historic Value’: The Records of Department of State Posts in Revolutionary Russia,” National Archives, Spring 2008, Vol. 40, No. 1, https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2008/spring/langbart.html.

[74] Gatewood, American Observers, 9.

[75] Gatewood, American Observers, 64.

[76] Gatewood, American Observers, 10.

[77] Gatewood, American Observers, 65 ff.

[78] “Maddin Summers suddenly dies in Moscow; Head of American Consulate in Bolshevist Capital Collapsed from Overwork,” The New York Times, May 6, 1918, https://www.nytimes.com/1918/05/06/archives/maddin-summers-dies-suddenly-in-moscow-head-of-american-consulate.html.

[79] Navasky, “Poole, DeWitt Clinton Jr.”

[80] DeWitt Clinton Poole, An American Diplomat in Bolshevik Russia (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2014), 100.

[81] Carr, “The Lenin Plot.”

[82] About Boris Savinkov see: Jeffery T. Richelson, A Century of Spies: Intelligence in the Twentieth Century (Oxford University Press, 1997), 59 ff., https://books.google.ch/books?id=9X5a1fgKqewC&q=boris+savinkov.

[83] “… in a telegram sent to London in the summer of 1918, Lockhart appears to be discussing the possibility of assassinating Lenin with Lord Curzon, who was a member of the British War Cabinet. After announcing his support for the Bolshevik adversary [Boris] Savinkov, Lockhart also mentions Britain’s participation in the conspiracy. Here is a quote: ‘Savinkov’s proposals for a counter-revolutionary coup. Plan: after the intervention of the Entente, the Bolshevik barons are killed and a military dictatorship is established.’” Eleanor Harding, “The plot to assassinate Lenin was ‘planned by Britain,’” MailOnline, March 22, 2011, available in Russian: https://web.archive.org/web/20131227201759/http://rus.ruvr.ru/2011/03/22/47809399/.

[84] Gatewood, American Observers, 11.

[85] Gatewood, American Observers, 11.

[86] Besides Bakthmeteff, there were several figures that served as “quasi-ambassadors” in the Interwar Period which would step into the diplomatic void, such as Maxim Litvinov, Ludwig Martens or Boris Skvirsky.

[87] Donald Davi and Eugene Trani, The First Cold War: The Legacy of Woodrow Wilson in U. S.-Soviet Relations (Columbia and London: University of Missouri Press, 2002), 138 ff., https://archive.org/details/firstcoldwarlega00davi_0/page/138/.

[88] Clifford Kinvig, Churchill’s Crusade: The British Invasion of Russia 1918–1920 (London: Hambledon Continuum, 2006), 29.

[89] Kinvig, Churchill’s Crusade, 34–35.

[90] Kinvig, Churchill’s Crusade, 38–39.

[91] P. A. Golub, “Interventsiya i Belyy Terror Na Severe Rossii,” Zhurnal «Politicheskoye Prosveshcheniye» 55, no. 2 (2010), https://www.politpros.com/journal/read/?ID=136.

[92] Gatewood, American Observers, 70.

[93] Gatewood, American Observers, 76–78.

[94] Evan Mawdsley, The Russian Civil War (Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2011), Chapter 11 (electronic version); Ross, De Koutiepov à Miller, 8.

[95] Gibson Bell Smith, “Guarding the Railroad, Taming the Cossacks: The U.S. Army in Russia, 1918–1920,” Prologue Magazine, Winter 2002, Vol. 34, No. 4, National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2002/winter/us-army-in-russia-1.html.

[96] Committee on Military Affairs United States Congress. House Committee on Military Affairs, Russian Railway Service Corps, Providing an Honorable Discharge for The Members Of, From The Military Service Of The United States (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1922), http://archive.org/details/russianrailways00housgoog.

[97] Gatewood, American Observers, 73.

[98] Foglesong, America’s Secret War, 75.

[99] Gatewood, American Observers, 74.

[100] John Silverlight, The Victor’s’ Dilemma: Allied Intervention in the Russian Civil War (New York: Weybright and Talley, 1971),

https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Victors_Dilemma/LNloAAAAMAAJ?hl=de&gbpv=1&bsq=“unconditionally+and+in+whatever+capacity.

[101] Peter Fleming, The Fate of Admiral Kolchak (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World Inc., 2001), 33 ff., 55, https://archive.org/details/fateofadmiralkol0000flem.

[102] Jonathan D. Smele, Civil War in Siberia: The Anti-Bolshevik Government of Admiral Kolchak, 1918–1920 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 2.

[103] Ian C. D. Moffat, The Allied Intervention In Russia, 1918-1920: The Diplomacy Of Chaos (Houndsmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), 242.

[60] “… [in December 1917] President Wilson had authorized aid to anti-Bolshevik forces in the Don and Caucasus regions. Since the Wilson administration was unable to give official U.S. funds directly to groups that were neither recognized governments nor belligerents in the war against Germany, it was necessary to find indirect methods of financing. The administration therefore promised British leaders that it would reimburse them for support to the Whites. Over several months, from late 1917 through the spring of 1918, U.S. officials worked with British counterparts in efforts to transmit funds.” Foglesong, America’s Secret War, 77.

[61] Foglesong, America’s Secret War, 78 ff., 92–93.

[62] Foglesong, America’s Secret War, 92.

[63] Foglesong, America’s Secret War, 93.

[64] David R. Francis, “The Ambassador in Russia (Francis) to the Secretary of State,” No. 1036, Petrograd, January 24/February 6, 1918, Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, 1918, Russia, Volume II, File No. 861.00/1707 https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1918Russiav02/d732.

[65] Foglesong, America’s Secret War, 92–93.

[66] Joseph King, Three Bloody Men: Mannerheim, Denikin, Koltchak (Glasgow: Reformers Bookstall, July 1919), 6, http://russianrevolution.marx-memorial-library.org.uk/mml-three-bloody-men-by-joseph-king/.

[67] Nicolas Ross, De Koutiepov à Miller: le combat des russes blancs 1930–1940 (Editions des Syrtes, 2017), 7.

[68] Ross, De Koutiepov à Miller, 8.

[69] Ross, De Koutiepov à Miller, 8.

[70] Paul Robinson, The White Russian army in exile, 1920-1941 (PhD thesis, University of Oxford, 1999), 6–7.

[71] Ross, De Koutiepov à Miller, 9.

[72] James Gatewood, American Observers in the Soviet Union 1917-1933 (University of Wisconsin, 1968), 7. James Gatewood’s thesis extensively covers the scope of American presence during the revolutionary years in Russia and beyond, including many first-hand accounts.

[73] “Since he expected a quick return to Petrograd, Francis directed staff to take only records needed for current business. The staff burned the previous 10-year accumulation of sensitive files and left the remaining records in the care of the neutral Norwegians, who assumed responsibility for American interests in Petrograd. One vice consul remained in the city to gather information and to take care of consular business.” David A. Langbart, “‘No Little Historic Value’: The Records of Department of State Posts in Revolutionary Russia,” National Archives, Spring 2008, Vol. 40, No. 1, https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2008/spring/langbart.html.

[74] Gatewood, American Observers, 9.

[75] Gatewood, American Observers, 64.

[76] Gatewood, American Observers, 10.

[77] Gatewood, American Observers, 65 ff.

[78] “Maddin Summers suddenly dies in Moscow; Head of American Consulate in Bolshevist Capital Collapsed from Overwork,” The New York Times, May 6, 1918, https://www.nytimes.com/1918/05/06/archives/maddin-summers-dies-suddenly-in-moscow-head-of-american-consulate.html.

[79] Navasky, “Poole, DeWitt Clinton Jr.”

[80] DeWitt Clinton Poole, An American Diplomat in Bolshevik Russia (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2014), 100.

[81] Carr, “The Lenin Plot.”

[82] About Boris Savinkov see: Jeffery T. Richelson, A Century of Spies: Intelligence in the Twentieth Century (Oxford University Press, 1997), 59 ff., https://books.google.ch/books?id=9X5a1fgKqewC&q=boris+savinkov.

[83] “… in a telegram sent to London in the summer of 1918, Lockhart appears to be discussing the possibility of assassinating Lenin with Lord Curzon, who was a member of the British War Cabinet. After announcing his support for the Bolshevik adversary [Boris] Savinkov, Lockhart also mentions Britain’s participation in the conspiracy. Here is a quote: ‘Savinkov’s proposals for a counter-revolutionary coup. Plan: after the intervention of the Entente, the Bolshevik barons are killed and a military dictatorship is established.’” Eleanor Harding, “The plot to assassinate Lenin was ‘planned by Britain,’” MailOnline, March 22, 2011, available in Russian: https://web.archive.org/web/20131227201759/http://rus.ruvr.ru/2011/03/22/47809399/.

[84] Gatewood, American Observers, 11.

[85] Gatewood, American Observers, 11.

[86] Besides Bakthmeteff, there were several figures that served as “quasi-ambassadors” in the Interwar Period which would step into the diplomatic void, such as Maxim Litvinov, Ludwig Martens or Boris Skvirsky.

[87] Donald Davi and Eugene Trani, The First Cold War: The Legacy of Woodrow Wilson in U. S.-Soviet Relations (Columbia and London: University of Missouri Press, 2002), 138 ff., https://archive.org/details/firstcoldwarlega00davi_0/page/138/.

[88] Clifford Kinvig, Churchill’s Crusade: The British Invasion of Russia 1918–1920 (London: Hambledon Continuum, 2006), 29.

[89] Kinvig, Churchill’s Crusade, 34–35.

[90] Kinvig, Churchill’s Crusade, 38–39.

[91] P. A. Golub, “Interventsiya i Belyy Terror Na Severe Rossii,” Zhurnal «Politicheskoye Prosveshcheniye» 55, no. 2 (2010), https://www.politpros.com/journal/read/?ID=136.

[92] Gatewood, American Observers, 70.

[93] Gatewood, American Observers, 76–78.

[94] Evan Mawdsley, The Russian Civil War (Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2011), Chapter 11 (electronic version); Ross, De Koutiepov à Miller, 8.

[95] Gibson Bell Smith, “Guarding the Railroad, Taming the Cossacks: The U.S. Army in Russia, 1918–1920,” Prologue Magazine, Winter 2002, Vol. 34, No. 4, National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2002/winter/us-army-in-russia-1.html.

[96] Committee on Military Affairs United States Congress. House Committee on Military Affairs, Russian Railway Service Corps, Providing an Honorable Discharge for The Members Of, From The Military Service Of The United States (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1922), http://archive.org/details/russianrailways00housgoog.

[97] Gatewood, American Observers, 73.

[98] Foglesong, America’s Secret War, 75.

[99] Gatewood, American Observers, 74.

[100] John Silverlight, The Victor’s’ Dilemma: Allied Intervention in the Russian Civil War (New York: Weybright and Talley, 1971),

https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Victors_Dilemma/LNloAAAAMAAJ?hl=de&gbpv=1&bsq=“unconditionally+and+in+whatever+capacity.

[101] Peter Fleming, The Fate of Admiral Kolchak (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World Inc., 2001), 33 ff., 55, https://archive.org/details/fateofadmiralkol0000flem.

[102] Jonathan D. Smele, Civil War in Siberia: The Anti-Bolshevik Government of Admiral Kolchak, 1918–1920 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 2.

[103] Ian C. D. Moffat, The Allied Intervention In Russia, 1918-1920: The Diplomacy Of Chaos (Houndsmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), 242.